Alan Cooper has more energy than a locomotive, and he thinks faster than a speeding bullet. He must type pretty fast too, because he’s provided us with some of the most helpful books in user interface design and yes, dare I say it, personas. Alan’s description of personas lit up our discipline like the Daily Planet building, and his ideas are still a sizzling topic of conversation. His history reads like a who’s-who of influential people and radical technologies. And now? Well, of course…he’s back into thinking lots and lots about trains, which were his very first love.

Interview Excerpts:

So when I was wandering in Zurich in 1972, I saw one of these banks with basement windows. Looking down into the basement, I remember I saw this computer. It was an IBM 360 and it had this panel covered with lights and buttons and switches and knobs. I stood there looking at it, and I said ‘I’m going to learn what all those buttons, knobs and lights are for.’ A couple of years later, I did: They are there to impress people. That’s their main role.

There are a lot of people who think that we’ll solve the problem by getting programmers to be interaction designers. I think that’s totally wrong. Why would you take perfectly good programmers and have them do anything other than programming? What you do is you have the interaction designers do interaction design.’

Full Interview:

Conducted by Tamara Adlin on September 24, 2007

Only Alan can explain Alan: “I programmed like a crazed weasel. I loved it. I took to it. It was my natural thing.”

.He is also the founder of Cooper, originally called Cooper Interaction Design, which is a very well known and respected interaction design and user experience consultancy. When you were a kid, what fascinated you?

sets. I didn’t have Legos because we didn’t have Lego in the United States back then, but I had Lego-like things, like Erector Sets. I liked designing and building.

At my high school, they had two classes in architecture. I took them both as many times as I could. That’s what I wanted to do.

Interestingly, I never did go to university to study architecture like I wanted. I ended up getting seduced into the software world. But building software is just like architecture. It is the exact same thing. In fact, as an inventor and writer of software, I believe that I do more architecture than my contemporaries who went on and became actual building architects.

Very few actual building architects these days can actually conceive of entire buildings and then see them realized. And yet it’s possible to conceive of an entire piece of software and see it realized; it is very much an architectural process.

I think architecture is a craft, and it is an interesting craft in that it combines deeply technical stuff with an aesthetic sense and a purposeful human side. Architecture without the humans is engineering. Buildings do need to be engineered, but architecture is the part that says, “What’s the human problem we’re trying to solve?”

Software design is not pure engineering, though engineering is one of the legs of the tripod. It’s about solving human problems. You have to understand the human side of things.

So many programmers are so focused on the technical stuff. They see their role as solving the technical problem, implementing the task, or implementing the feature. This part absolutely needs to be done, but it needs to be done under the umbrella of what the human user is trying to accomplish.

In the early ’70s there were a lot of riots around the country. There were all these free speech riots in Berkeley, when students would go rampaging through the streets. I happened to be one of those – I wasn’t a student at the time, I was a drop in, an outside agitator – but I would come to town. I was a nice guy; I didn’t go breaking windows and stuff. I would hang out for the excitement and to try to meet women.

But rocks and bricks and stuff did get thrown through these windows, and these very expensive computers in the basement would get trashed.

So when I was wandering in Zurich in 1972, looking down into the basement of some bank, I saw an old IBM 360. It had this panel covered with lights and buttons and switches and knobs. I was very impressed. I stood there looking at it, and I said, “I’m going to learn what all those buttons, knobs and lights are for.”

A couple of years later, I did: They are there to impress people. That’s their main role.

When I came home, I enrolled in a community college and took a class in programming. Within a few weeks I discovered that programming was the magical wonderful place where you could build structures of magnificent scope and complexity and interest, and you had absolute control over them. You could do it all by yourself. You were in your own private universe where you could create your own private world. I was utterly seduced by it.

I took the introductory programming class because I thought it would be a good way for me to work part time to make enough money to pay my way through architecture school. That’s what I expected to do, and that’s how I saw it.

I just kind of got sucked into this whole programming thing. A friend of mine, who was actually a programmer at the time, said, “You should go out and work. You’re a better programmer than most of the guys I work with.” I said I’d give that a try.

So I went out and got a job programming.

[laughter]

People would say, “We gotta get one of them there computers to do our accounts receivable,” so they’d go buy the computer, then they’d go to the accounts receivable accountants and say, “You guys are accounts receivable, program this computer.”

They discovered that accounts receivable clerks didn’t know how to program computers. It turned out programming was a specialty in and of itself. Then there arose the nasty question of how you identify who could be a programmer. They would have chess contests, IQ contests… It was a real problem.

We have a similar problem today. People ask me, “How do you identify an interaction designer?”

I was the most junior guy with the longest hair, and I was handed the cheesiest module of COBOL code that had ever been written and told to do something with it.

I started spelunking in this spaghetti code. It was the worst stuff in the world.

American President Lines had a fleet of 22 steam ships they’d send all around the world. They would sail for a month or more between ports, and when they’d get to a port they would pull in, unload cargo, and load up new cargo. Then they would sail on.

Six months later, the bill for stevedoring in Jakarta or Singapore or Rangoon or wherever they did this cargo handling would show up back at headquarters in San Francisco. But the cost was incurred at the time of offloading, so they needed to get that information to their accountants sooner.

The port master would telegraph a scratch total from Jakarta or Rangoon or wherever. It would say we unloaded 150 tons and we loaded 200 tons.

This program said, “We don’t know exactly how much it costs to unload a ton, but based on the exchange rates and what it cost last time, I know it’s approximately $8/ton.” It gave the accountants an interim number to work from so they could get an estimated cost of doing business that was reasonably current, knowing that they’d have to make an adjustment six months later when the actual bill showed up.

The program ran for four hours a day. It actually used the entire mainframe for four hours a day.

So one day spelunking through this program, I came across this tyromistake where the programmer who had written it –

Basically, his code unnecessarily re-read every record as many as 1,000 times. I saw this and said, “This doesn’t look right,” and I spent a couple of days poking around to make sure there wasn’t anything hidden going on. I finally commented out one line of code – the one redundant read – and ran the program the next day. It took four minutes to run and it worked perfectly.

There’s always been this hierarchy in the programming world. The systems programmers who deal close to the metal with pure algorithms always look down on the applications guys.

At the time, I had a friend who was a brilliant systems programmer; one of the smartest guys I’ve ever met. We decided to start our own company.

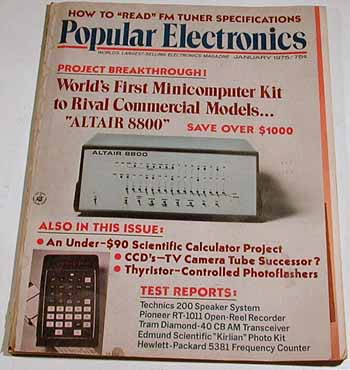

In 1975 he went traveling, and while he was gone I found this ad for a microcomputer – they didn’t call them personal computers back then. The very first microcomputer was an Altair.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="430"] The Altair 8800 on the cover of Popular Electronics (Source: http://www.computermuseum.li/Testpage/POP-ELEC-Altair-Jan75.jpg)[/caption]

The Altair 8800 on the cover of Popular Electronics (Source: http://www.computermuseum.li/Testpage/POP-ELEC-Altair-Jan75.jpg)[/caption]

When my friend came home from his travels, I showed him the ad and said, “Look at this, you can buy your own computer.” He looked at it and said, “What we should do is find some accountant who is ready to spend $20,000 to buy a minicomputer accounting system and instead charge him $10,000, take the money, go write one of these accounting systems, and give it to him. Then we can keep the software and go buy another computer, and we’d have a business.”

I said, “You know, it’s funny, I was at a party the other day and I was talking to a guy who’s an accountant, and he was just about to buy one of these minicomputer systems.”

He said, “Go talk to him. Let’s see if we can do this.”

So I went and talked to this accountant and he said, “Actually, that sounds like a good idea,” and he said he would do it.

My partner and I each ponied up some money, $7,000 each. We bought a computer and used that money to keep our company going while we sat down and wrote a general ledger accounting system.

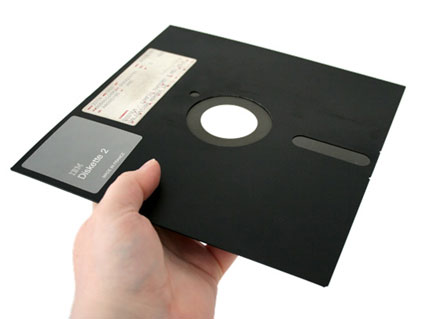

The first computer we bought had 48K of main memory and two floppy drives. They were for 8″ floppies – not 5″, but 8″ floppies – and they had 170K of storage. Not meg, not gig. K.

An 8″ floppy disk (Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/yaal/162100723/)

We met this guy named Gary Kildall, who was a professor at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. Gary Kildall was one of those incredibly brilliant guys who is very much one of the fathers of our industry, and is kind of an unsung hero, I think.

Gary had been doing some consulting work for Intel, who at the time was making the only microprocessor out there – the 8080. He had written an operating system for them called CP/M, and one of his graduate students, a young naval officer named Gordon Eubanks, had written a basic language compiler for his master’s thesis. We took the operating system and got it to work. It was about as primitive as you could get, but it was actually more powerful in some ways than what you could get from IBM in those days.

The language didn’t have decimal arithmetic in it – try writing an accounting program without decimal arithmetic! The integer arithmetic it had was 8-bit, so you could only have integers as high as 32,767. Again, you have an issue there.

It was a first attempt to try to make some sort of a user-programmable, configurable program for accountants. I was learning a lot at the time and was really focused on this interface issue.

Our approach to this was not at all research based. There was no theory behind it. We were just building stuff, very much like the early days of the web. People just slung stuff up on the web to see what happened, and that’s what we were doing. A whole other decade passed before I began to focus on design as a distinct activity.

About that time, I had the same sort of life changing event that Bill Gates and Steve Jobs did – I visited Xerox PARC.

I saw the Alto, and I went home and changed the way I did software.

I spent the ’80s building software and selling it to publishers. I did some word processing software; I created one of the very first spreadsheets. It was quite advanced for its time.

Then I wrote a serial communications program and sold it to a publisher. After that I wrote a critical path project management program, which I sold to CA (Computer Associates). That became SuperProject. It was kind of the model for Microsoft Project.

I began to narrow the wedge of the pie that I worked on as I went. In the ’80s, I decided I just wanted to invent software; I didn’t want to do any of the publishing or production stuff. I would come up with an idea and sit down and build a prototype. Then I would take it to a publisher and say, “Look at this prototype,” and hopefully they would say, “I like this. Now let’s sign a contract and you go build this and we’ll publish it and move on.”

Keep in mind that in the ’80s there were literally hundreds of software publishers out there, and Microsoft just one of many. I had sold the project management program to Computer Associates, having written 100% of it myself. It was all my code. It was pretty cool, actually. At the time, there was nothing quite like it. There were programs that did critical path project management, but you had to enter long tables.

My program would draw a picture of your critical path on the screen or on paper. Because I “got religion” from Xerox PARC, I did this on the green screen, before mice. You hit a function button and a box would appear, and then you’d hit arrow buttons to move it around on the screen. Then you could enter two numbers and tie the box to another box, establishing a critical path dependency. Then it would do its critical path calculations. It was a fairly cool program.

I did a geographical information system, which was like Google Maps except I was using DIME files, which were the then-current geographical files that things like Google Maps and Google Earth are dealing with today. They didn’t have satellites going around taking pictures, or at least they certainly didn’t publish them at the time.

What you could get were line outlines of counties, so I began working with that.

This was a classic example of a product I invented but couldn’t sell. One of the reasons I couldn’t sell it was because, in order for it to do what I wanted it to do, I needed a real graphics application environment and nothing like that existed at the time. So I wrote my own.

That’s being a glutton for punishment. It was really kind of stupid. A friend of mine grabbed me, and literally, physically dragged me to a presentation of Microsoft Windows Version 1 somewhere in Santa Clara. He said, “This is what you want.”

I saw the presentation and said, “Yes, that’s what I’ve been working on; that’s what I need.” I’d much rather buy it from Microsoft than try to write it myself, because I was struggling as a one man band. I literally was at home trying to write Windows by myself.

I became an early adopter of Windows as an applications developer.

I started noodling with various pieces of software. I forget what I was working on, but one thing that just leapt out at me and probably anybody who used Windows at the time was “Holy shit, this thing is so much more powerful than MS-DOS – but it has a terrible user shell.” It was terrible.

You could write an application that behaved nicely, but if you were a user and you wanted to look in your directory to see what files you had, you had to use a Windows program that was stupider than anything that existed on MS-DOS.

It was obvious to everybody that the Windows shell sucked. They knew they had to do something about it, but it was a tough nut to crack. In my spare time I would noodle on ideas for something to replace the shell.

It was a tough problem. It’s like the Mac Finder or the Windows desktop interface – it didn’t really exist at the time. What should it be? Nobody was really sure.

One day, a friend of mine had taken me on a sales call to a client site at Bank of America. I met this IT guy at the bank headquarters who was talking about his problems fielding Windows to his 30,000 employees.

The problem was that some of his employees were high-level analysts who knew how to use computers and used them regularly; some of his employees were mid-level bank people who knew how to use computers, but that wasn’t a primary part of their job; and a lot of his employees were tellers with a high school diploma. They needed to be given a carefully delineated playground in which to work.

All of a sudden I had a flash of insight. I saw that the solution to the shell was to provide a “construction set” allowing people to build their own shells. The analysts could build the shell to run their sophisticated stuff. The mid-level managers could have a shell that hides all the complexity. The analysts could also build very simple, tightly bound shells for their tellers.

You could open up a window, go up to this little palette of widgets, click on a picture of a menu button, drag it down and drop it onto the window, and a new, working button would appear in the window. Then you could go up and drag a text box and drop it on the window and then right click on the button and drag a rubber band over to the text box, release, and it would now wire the push button to the text box.

Then you could push the push button, and it would send a piece of text over to the text box.

The idea was that you could visually program your own shell. For example, at the time, OS/2 was out there, and it was the dominant operating system. It had a shell. With this functionality you could recreate the OS/2 shell in Windows in about ten minutes.

It was a powerful thing. It was the first Windows app that had drag and drop. I also did things so that it would fully animate when you dragged stuff. Nobody had ever seen animation on the Windows screen before.

If you were the bank teller, you could have a screen that would have three buttons for the three applications you normally ran.

If you were the mid-level manager, you could have buttons that would launch stuff, and a little directory showing you only the files that you worked on.

If you were an analyst – if you were developing these systems at the higher level – you could have it be one way on Monday and then change it around as you were working so that it was a completely different user shell on Tuesday.

I had no formal methods. I was just asking people I ran into in my daily life. I ended up talking with Kathy Lee, a woman who was a traffic manager at an advertising agency, and I based a lot of my work on her.

It was kind of a humbling thing because in the end she found the program to be unusable. I was really learning the hard way, but the good thing is I found myself saying, “What would Kathy do? What does she want here?”

This was the beginning of the idea of personas. I did make the mistake of trying to design for Kathy Lee, although I have to say I kind of abstracted Kathy Lee, so that she became a persona in my mind.

There is enough of a programmer in me to not actually want to talk to users, and to find talking to users to be an ordeal.

Each of those obviously would be a persona role.

I didn’t know Bill Gates well enough at that point to call him up and say, “Take a look at this,” but I had some friends at Microsoft and asked them if they could get me in to see him. So we got invited in by one of his lieutenants.

This guy said, “Come on up; I’ll take a look at what you’ve got.” So I went to Seattle and met this guy. I forget his name, but it was just the two of us sitting in a conference room, and I whipped out my computer and started demonstrating the software.

He looked at it for about three minutes, pushed his chair back and said, “Bill’s got to see this.”

I continued demoing this to him, and he turned to the group of people and said, ‘why don’t we do stuff like this?’ I thought this was good.

At one point Tandy Trower, one of the guys in the room, said, “Why would anybody want this? What’s the point of this?” I was inhaling, ready to give him my pitch, when Bill turned around and started explaining why people would want this program. Then he turned to me and said, “We want to buy this. This is going to change how people work with computers.”

Well, if you are a Product Manager on OS 2, this is going to piss you off.

As soon as we did the deal we changed the name from Tripod to Ruby, because I had shown it to Lotus and a bunch of other companies. It was just a random project name. Now there’s a language called Ruby , but back then it was our code name.

We worked on it for a year. I put a team together, we built a program, and we went through a full QA cycle and delivered it to Microsoft. During that time Microsoft split from IBM, and bye went OS/2, but not before the OS/2 people sank Ruby because it could recreate what they were doing.

One of the things I had done was to tell the Windows guys I was throwing Tripod out and starting from scratch, which is the right way to build software.

They went ballistic. They said, “You’re doing what? You’re throwing out code? You’re going to be late. You’ll delay us all.”

Of course it turned out they were late and I was on time because I threw the code away. What’s valuable is what you know, not what you’ve written. These are classic modern programming techniques that Microsoft hadn’t figured out at that point, or at least not on the Windows team.

I’ve never been a big fan of BASIC. It’s a fine language for writing a hundred-line program, but it’s no good for writing big software. I found it embarrassing that any work of mine would be associated with the language.

But at the time, Turbo Pascal was just chewing up the languages.

QuickBASIC, which was Bill’s product, was a dead product because it had been conquered by Pascal and C. C was for professionals and Pascal was for amateurs.

I had written Ruby in C; it was my language of choice. It was a very powerful language, but it was like a knife with no handle. You could really hurt yourself if you didn’t know what you were doing. You had to be good.

Bill had his people take my visual programming front end, unplug my little language, plug in QuickBASIC, and thus was born Visual Basic. So I like to say I did the Visual and they did the Basic.

At that time, Microsoft was growing and people would work on a project for three or four months then move somewhere else. Nobody knew who I was or what was going on. All they knew was that here was a project, here was a bunch of code, and it moved around. One person somehow heard some rumors and ended up inviting me to the product roll-out.

I went up to Washington when they did the product roll-out. I was really kind of steamed when I saw it, but I bit my tongue and said good work.

Microsoft had taken my shell ideas and turned them entirely towards programmers. Ruby had been the very first application to deliver practical use of the Dynamic Link Library (DLL) facility in Windows. Not only did the program present functionality visually, but independent, third-party vendors could create functionality that would dynamically become a seamless part of the development system. At the time it was called the VBX interface, and it was an original invention of mine. VBX has morphed into OCX and ActiveX, but it has been the platform of choice for thousands of independent programmers.

.

He had seen my name in the “About” box in VB, so he called me up and said, “I’ve been using Visual Basic and I see it says Cooper. Is that you?” I said, “Yeah; that’s me.” He said, “Oh, God, you have to tell me the story.”

So we had lunch, I told this long story, and at the end of it he sat there with his jaw hanging on the ground, saying, “You’re the father of Visual Basic.”

I said, “Thank you.” He had just given me my one-line resume. When I call myself “the father of Visual Basic,” I’m quoting Mitch Waite.

At that point, the industry was consolidating. When I started work on it, there were at least 100 software publishers out there. By the time I was done, there was Microsoft and that was about it. Nobody really published software that they bought from outside. They either bought companies or rebuilt their own.

There was no solution to it. My wife asked me, “What is it you really want to do?” and I said, “I just want to design software but I don’t want to build it.” She said, “well, do that.” It stopped me. I didn’t know how I could possibly do that.

I thought being a consultant and working on other peoples’ software would be really stupid. I really thought there were two kinds of software: my software and bad software. It was the typical programmer’s arrogant approach to the world. But I said “Okay, I’ll give this a try.”

One day in 1992, I was hosing a panel discussion at a Windows conference in Boston. At the end of it, I turned to my panelists and said, “Hey you guys, I’m a consultant. You’re going to hire me.”

Two of them actually hired me. It was amazing. One of them was a short term deal, although he ended up coming back five, six years later and hiring me again. The other guy I teamed up with, John Zicker, turned into a long term consulting relationship. I helped him as he migrated through three separate companies that he started, grew, and sold.

She saw the enthusiastic reception I was getting as people listened to what I had to say, and said, “I agree with you; I think there is something here.” We decided to make a business; not just with me consulting, but to really make a business. That was in 1994. We hired our first employee, Wayne Greenwood, and we became Cooper Interaction Design.

I was working on a project John Zicker. That guy is brilliant and all the people who work for him are brilliant. They had a brilliant product.

It was one of the very first business intelligence programs; though it was before the name “business intelligence” had been invented. This product that would go into databases and suck out their marrow and put really cool information up on the screen that you could then massage in a bunch of different ways.

It was incredibly powerful. It was a classic software tool in that it could morph into anything you’d want. I’d sit down with John and say, “Who would use this tool?” and he would skitter allover the place. Anybody could use it for anything.

I couldn’t pin it down to who would use it for what, and was craving one real world example so I could sink my teeth into this thing. Finally, I said, “I need to talk to some of your clients,” because I was in this circular discussion and it went nowhere.

John let me have access to some of his clients, but I took along his director of marketing because they wouldn’t let me talk to them by myself. And this is how I went out and started doing some of my first client visits. I’m not a scientist – I don’t do research – but I just went in and said, “What do you do? What are the issues?” and I started listening.

The patterns leaped out at me. It was obvious within six or eight interviews exactly what was going on. Coincidentally, the patterns were very similar to the ones that the IT manager at Bank of America had talked about. Remember, he had analysts who thought out algorithms for analysis, analysts who used them, and then technicians who did data gathering.

In these cases you want three interfaces: One for people to create the tools, one to organize the tools, and the third for people who just need to use the tools. That was how we created the first three personas. Rob, Cindy and were the very first personas.

?

If you hold back and say, “I’m not going to talk about that until my next book,” your reader senses the stinginess and doesn’t like it. You have to say, “Here’s 100% of what I know,” with the faith that your reservoir will fill back up with more things to say.

My point was that testing is too late. You have to do proactive design in advance. I wanted to get that idea out on paper.

That company – it was called ReportSmith – was wonderful to work with. They were the classic software company with brilliant software people and run by brilliant managers. They thought if it was a brilliant program filled with all this incredible power, then that’s what they had. They had the sense to see that it wasn’t working, but they didn’t really see what the problem was.

I came in and introduced the personas with PowerPoint. I said, “Here’s Cindy,” and started describing Cindy and what she needed. All of a sudden, I could see I was getting through. The programmers were sitting there saying, “Oh, well I could see how Cindy would want THAT, and how THAT other thing would just get in her way.” I began to realize that I had something very powerful here.

I knew that this was a continuation of what I was doing when I was writing SuperProject, when I based my work off of Kathy Lee, the real traffic manager I had spoken to. I used to go out for long walks and say, “What would Kathy do in this situation? I know she’d want to have this information, but not that information.” I knew I was doing the same thing here with ReportSmith, it was just an extension or abstraction of it. And for the first time, I put names and faces to it.

I was thinking that this was just one of many tools we developed; other people will develop their own tools.

One of the reasons we have very powerful software with lots of features and no coherence is because you don’t have to write software with coherence for it to work, but you do have to write it with features. Software is very much a representation of the way it’s built internally.

If you come at it from a user’s point of view instead, then you’re not necessarily going to organize it feature by feature. The way you get the vision to do that is through the personas. It all hangs together.

I was very pleased. Chapter 9 in Inmates was about personas, chapter 10 was about scenarios, and chapter 11 was about goals. It was very specific. What I was trying to say is that I am not just blowing smoke. That’s what I told myself as I was writing the book.

I didn’t see the book as a how-to for practitioners at all. I saw it as something to help business people see that not only is there a reason they should adopt user-centered design, but if they did they were adopting something very sophisticated and practical.

It was a very pleasant surprise to me to find that people were really understanding personas and starting to use them.

I said that a wrong persona is better than no persona. A lot of people have taken me to task for that because they think I am advocating arbitrary personas, and I’m not.

What I am saying is – and I’ve said this to guys at Microsoft – you’ve got 40 million people who use Microsoft Word and they all hate the program. What if you were to pick one representative archetype and design for that one person? Just make that one person ecstatic. If that person is at all representative, it means you’re going to have 10 million other similar people who are also ecstatic.

The end result is 10 million newly ecstatic users and 30 million users who feel the same way about it as they did before, which is a significant improvement.

It was a car designed for somebody who represented everybody, and that somebody was the person who couldn’t afford the big fancy giant cars. Another car that’s very successful in that way is the Porsche 911, which is again a car designed for a very, very narrow target market.

It just so happens to be a narrow target market representative of a verynarrow target market, whereas the Volkswagen was designed for a very narrow target market representative of a very large target market.

What’s interesting about the Volkswagen and the Porsche 911 is that they are both companies and brands that have stood the test of time. They are automobiles that continue to be produced today 50 to 60 years after their introduction, that are globally recognized, and that are standards upon which there have been many, many variants.

You may have a different market than you intended, but you’ll have a success. It is really hard to get programmers who think mathematically, to think about focusing on a single person, which is actually good.

There are a lot of people who think that we’ll solve the problem by getting programmers to be interaction designers.

I think that’s totally wrong. Why would you take perfectly good programmers and have them do anything other than programming? What you do is you have the interaction designers do interaction design.

So what you do is you go to the programmer, and instead of saying “I think the window should be smaller,” you say, “Jane Johnson would want a smaller window, and here’s why.”

All of a sudden it’s no longer your ego against his. Now he can say, “Oh, that’s what Jane Johnson wants; okay. I understand that.”

The persona becomes a very powerful tool for enabling communication by de-polarizing; by grounding out all of that competitive energy. That’s one of the great strengths of personas.

has just come out…

But I began to have a lot of insight into how software gets built. It’s one of the side benefits of being a consultant and having hundreds of clients and thousands of engagements, and having those clients be big companies, little companies, software companies and product companies and service companies, and have them be all over the world.

You start seeing patterns, and the patterns are really clear. I began to realize that the problems we were experiencing were not problems in software design, and they were not problems in usability. The problems we were seeing over and over again were the problems in software construction.

Fifteen years ago, programmers built software without blueprints. Over the last 15 years, we’ve learned how to draw beautiful blueprints of great design and high-quality that are very communicative, very powerful, and very effective.

When you put those blueprints in front of programmers, what we’ve discovered is that the programmers don’t follow them. It’s not because they are dumb – they are anything but. A lot of it is systemic. The corporate organizations are organizations that know how to build software, but they’re not used to building software from a plan.

They are actually optimized to build software without plans, so everything about the process is based on doing something now, assuming you don’t know what’s going on tomorrow. When you have a plan you know what’s going on tomorrow, so you make different decisions.

I began to see that the problem was organizational and managerial. I began to tell my clients this. I discovered, much to my chagrin, that my clients didn’t want to hear this.

After a couple of years of trying to bang this drum, I realized one of two things is true: Either I am completely full of crap, or there’s a real opportunity for me to set up a software company based on this new paradigm of software construction.

I decided I should go ahead and create a software company; it’s time for me to get back to building a software product.

I couldn’t raise money because investors are business people, and they look at it from a business point of view. They’re willing to take risks, but they’re not willing to take leaps of imagination.

At that point, I said, “Okay, it’s time to build a model railroad.” So that’s what I’m doing. I’m building a model railroad.

This summer I’m going to be taking another trip back to the Midwest, tracing the old railroad routes, taking pictures, and doing research in historical societies. I’ll be in Indianapolis gathering information so I can come home and continue working on my model trains.

© 2020 Adlin Inc. All Rights Reserved.

© 2020 Adlin Inc. All Rights Reserved.