John Carroll is another pioneer who ‘accidentally’ ended up with two degrees (because he took so many courses to satisfy his diverse interests) and whose career was majorly influenced by having a year to kill. That one years…spent at Watson Research Center…turned into 18. How many other people, who describe themselves as having the ‘soul of a psychologist,’ can tell you stories about the very first times the ‘user’ became an interesting topic of conversation at IBM? How many have participated in the development of the HCI field from inside a major corporation and academia and the birth of a professional association? How many have worked with Noam Chomsky only to decide they didn’t want to be a linguist? Well, at least one. And today, he’s interested in all of the interesting challenges of teaching, which is awfully lucky for the students at Penn State. Confused about what you want to do with your life? Don’t worry…according to John, it will all look simple once you get there.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW

I actually don’t like the term ‘user’ very much at this point. I’ve gotten tired of it. It is homophonous with a “drug user”. And it seems to make people passive and one-dimensional. I tend to try to pinch myself and replace it with person or something more interesting… But oddly, the term “user” with all its flaws, was very important early on. It conveyed to the technology people that the arcane software they produced eventually had to be USED. It was a focus for the emerging professional identity of CHI people.

There’s a rough side to interdisciplinary – maybe you already know this – everybody disagrees about everything – they all came from a different place, they’re trained in a different way; they have different values and so forth, so it’s not like it’s living in heaven. But it is very interesting. It’s very rich. And it’s not so narrow and alien the way it would be, I believe, if I had gone into that engineering college with my colleagues.

AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN CARROLL

Conducted by Tamara Adlin on October 3, 2008 08:56 AM

John reminded me that “everything you do changes the rest of your life.” And in his case, it can also help build a whole new field.

He served on the Program Committee of the 1982 National Bureau of Standards Conference on the Human Factors of Computing Systems. That was particularly interesting because it, in effect, inaugurated the field and was the direct predecessor of the field’s flagship conference series, the ACM CHI Conferences.

For the past two decades, John Carroll has been a leader in the development in the field of human computer interaction. He has published several books, including Designing Interaction: Psychology at the Human-Computer Interface and Making Use: Scenario-Based Design of Human-Computer Interactions

.

Today he is the Edward M. Frymoyer Professor of Information Sciences Technology at Penn State.

Hello!

Even as an undergraduate, I struggled with these two interests; majoring in a lot of different things. I ended up as a math major but really just as a compromise among many interests. Then I went to graduate school in psychology and linguistics, so I swung back the other way.

I think this tension was resolved for me eventually by getting into human computer interaction. But it was largely accidental. I had been a graduate student at Columbia, and I got my PhD in Psychology. But as I was explaining, I always liked math too so in psychology, I specialized in the Psychology of Language – at that time it was called Psycholinguistics. This meant I took a lot of linguistics courses, worked on transformational-generative grammars, and so forth.

Anyway, when I finished graduate school, I interviewed extensively in psychology and linguistics departments but I didn’t find anything suitable. I went to the IBM Watson Research Center for Post Doc year. My girlfriend at the time was one year behind me at Columbia. I thought, well, I’ve got a year to kill. I’ll just take the Post Doc that will pay me the most, hang out for a year, and have a better interview season next year.

It is very interesting to me that one person could be so interested in both math and psychology. What were the other things you were considering too?

So in fact, I wound up with two bachelor’s degrees; one in Information Science and one in Mathematics. One of the things that can happen when you don’t know what you want to major in, and you just take a lot of courses, is that you end up with enough courses to get two degrees.

When I got the Information Science degree, no one seemed to know what it meant. But ironically, the department I am in at Penn State now is called Information Sciences and Technology.

I also should say, I’m really not a flakey person; in fact, I would say despite the fact that I ended up living my professional life with software engineers, designers, and computer scientists, I always have conceptualized things as a psychologist.

There’s something about the apprenticeship of graduate school, maybe – or maybe psychology just really was the right identity for me – but I feel I have the soul of a psychologist; that’s really what I am.

As everybody who has pursued an academic career knows, there are so many universities, but for any given PhD student, any given scholar or scientist, there is a far smaller number that are appropriate, and might actually be looking for a faculty member with your particular skills and interests.

So if you wait a year, you really get a chance at a whole different set of job opportunities. It wasn’t an irrational thing to do, and it also made personal sense because I would have had to settle for less, and also move away from my girlfriend.

I went to the Watson Research Center, which was an absolutely excellent place in linguistics, and also had a very good research staff in cognitive psychology. However, going directly from being a psycholinguist at Columbia to an industrial lab in 1976 was not the normal career path. It surprised my Columbia colleagues. But it really was not that shocking. There were lots of wonderful colleagues at Watson from the start. It was actually quite awesome to ponder the quality of the scientists that worked there. They certainly covered all of my interests.

You have my bio, so you know I stayed there for 18 years, not just one year, as originally planned.

She knows this story, of course, and has heard it too many times, but she heard it again last night. She’s asking herself what should she major in, and I said, well, of course, you’d like to pick the thing that 20 years from now will be the “right” choice, but how can you do that. There’s no way we can ever do that. Too many unpredictable things will happen.

What did you do and love in the early years you were there?

Plus, on the linguistics side, Watson had some outstanding people too; David Johnson, Paul Postal, Warren Plath, Stan Petrick, John Sowa – so between the two of these groups, I had a wonderful collegial support.

I spent the first years of my IBM career working on psycholinguistics, on the one hand – I studied referring expressions, and, on the other hand, studying software design as a kind of boundary case of problem solving; what everybody now calls ill-structured problem solving or wicked problem solving.

Those are both really interesting questions; academically, scientifically, in their own right, and very sustaining things to investigate. It really helped me grow a lot, I think, as a professional and as a scientist.

Nevertheless, I wasn’t completely grown up and committed to what was becoming HCI yet. Because when I had the chance in 1980 to go to MIT as a kind of a senior Post Doc, and to work for a year with Noam Chomsky, I did it.

In the 1970s, industrial research institutions were fundamentally different than they are now. In the context of the Cold War and Sputnik, and American global economic dominance, a far greater proportion of GNP was being directed to basic science than is the case now. I won’t be so indelicate as to ask you how old you are – but I’m guessing you are younger than me.

The companies only expected a certain portion of that to really end up in their product plans, ever. That’s kind of an alien idea today, isn’t it. Today everything is much more ROI.

President Kennedy’s goal of getting to the moon was intended to send a Cold War message to the Russians and the rest of the world. But it also was clearly all about big ambitions, human achievement, and hope. If we think about our own industry – computing, the 1960s were the years when the computer as we know it was being invented. Lots of big things were happening; cognitive psychology and modern linguistics were invented in that decade.

But that’s not a company doing it; it’s the government straight to academia.

Anyway, I decided to take a break from Watson, and to go to MIT and refocus on linguistics and cognitive science. Honestly, a big part of the attraction was the chance to study with Chomsky. His impacts on more or less everything I had studied or worked on was huge. He was my PhD advisor’s advisor, so indirectly, for me, he was the source.

I went to MIT for the academic year 1980-1981. It had an unexpected effect on me. I thought and I hoped it would help me decide what to do, where to direct myself,and it did. Working with Chomsky, and being at MIT made me absolutely certain I did not want to be a linguist.

It didn’t interest me as much as I thought it would. Many of the key issues in transformation-generative grammar seemed remote from any empirical consequence.

But I did not want to be a linguist after that year. I am still interested in language, still fascinated, but I wanted to do something different as my own science. It was wonderful timing for me, because, immediately before I had left IBM for MIT, we had held a corporate task force, of which I was a member. That task force recommended that IBM should be much more ambitious in the areas of cognitive science, cognitive psychology, and use interface design – we didn’t yet have the term human computer interaction. It set a new strategic direction for IBM Research. When I returned from MIT, the recommendations were being implemented.

These new directions were also directly supported by changes in the business environment and throughout the corporation. In the 1970s, of course, IBM was all about big iron and professional programmers, but as the 80s came, we were getting positioned to become the PC company, and everybody else was too.

This was a very fundamental change for IBM. It changed who was the user and who was the customer. Some of these changes are still being assimilated in our industry. I had been studying programming as a kind of problem solving before I went to MIT, because when we talked about people and computers, we automatically thought of programmers the problems of professional programmers. That was the 70s.

The task force I served on in 1980 wrote a report, as task forces often do, and then followed through by presenting the results and recommendations to IBM executives in the Research Division and elsewhere. By the time I came back from MIT, there clearly had been a sea change at IBM with respect to psychology; different departments, different groups, different managers. We were hiring a lot of people. We were rapidly getting focused on the problems with naïve, novice users, general users, business employees learning and using computers to do regular work, not programming.

But by 1981, when I returned from MIT, suddenly it was a whole different set of problems. It was computers and kids; computers and secretaries; computers and office principals.

I made my personal decision, and I did not have worry about wallowing in self doubt. There was way too much to do. As you mentioned in your introduction, the spring of 1982 was the Gaithersburg Conference – at the National Bureau of Standards, which is now NIST. That was essentially the zero’th CHI Conference.

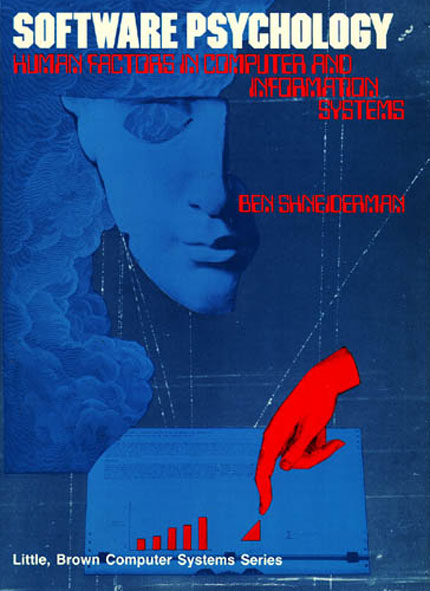

I first met Tom Moran and Stu Card, and Tom Malone at Gaithersburg. I knew Ben Shneiderman from before, but I met a lot of his software psychology associates at Gaithersburg. Wow; it was an exciting three days.

It wasn’t an accident that this event was held in the Washington, D.C., area. That was a hub for the software psychology interest area, which was one of the most important constituencies of the early CHI group. It’s interesting and ironic; you look at CHI today, and there’s not a lot of focus on the psychology of programming. The field has evolved.

It’s evolved toward the end user, towards interactions and the experiences of interactions. The problems of software professionals, or even non professional programmers are not really central now. Gaithersburg helped to start a rescoping of the early research focuses of CHI: cognitive user models – like GOMS, interaction with menus and commands, games as a framework for learning.

![]() , I think, but that was 1983. Of course, they were working on that book for several years.

, I think, but that was 1983. Of course, they were working on that book for several years.

Another interesting footnote in the history of CHI is that role of the Human Factors Society and the many human factors people who are interested in computers. Today, we identify professions like usability engineer and interaction designer, even user experience designer. But in the early days, it was human factors engineers, and documentation designers. That human factors constituency was critical in the early days. I was a part of it.

People like Dick Pew, Alphonse Chapanis, Robert Williges, and my colleague at Watson, John Gould were very established human factors guys who got interested in this CHI project and gave it a lot of support early on. Like the psychology of programming, the human factors influence in CHI has fallen away over the years. I don’t know if that’s good or bad; I guess I’d be inclined to think it’s bad, but it’s true.

I would say the paradigmatic problem in human factors now is as contrasted, say, with CHI, is more that they are more interested in control systems; like air traffic control or semi automated factories or piloting planes and boats – those are the things they seem to focus on or gravitate toward more than, say, digital camera interfaces, composing and posting photos on Flickr, etc.

You do not hear much about control system issues in CHI.

You can’t blame a community for having a finite scope. A professional community would lose coherence if it tried to keep too many things in focus. And CHI has many, many things in its focus! As time goes by, some topics, and the people who study them break away to form their own communities. Human factors slipped out of the focus for CHI, as did the psychology of programming.

In those cases it is just especially ironic because human factors and the psychology of programming were so central and so important to the early CHI community.

I remember discussing CHI ’86 with Stu Card, and talking about whether we needed to make an adjustment that year through the program committee process to be a little more solicitous to the cognitive people. I don’t think we need to do that as deliberately now. The community has its own momentum and it will go on.

Maybe it will be a little less or more cognitive but I don’t think people think they need to manage the balance. But in those years we did.

I feel it was a pretty good growth trajectory.

For me, the next big thing that happened was in 1984 which is when at Watson, we formed the User Interface Institute. This was a big thing professionally for HCI and usability and user interface people in IBM. Up to that time, some of us were human factors people, some of us were user interface programmers but there wasn’t an appreciation that this was its own multifaceted community that spanned both of those things, and that it was an integral part of the IBM professional community.

It also helped the HCI area grow at Watson. In one particular year, I remember we got ten new head count, and we became a second level organization which meant there was a senior manager of user interface research – for the first time ever in IBM.

So you were in the position, even that early, of trying to find people who would be really good at this. For people who have been in that position before, I like to ask how did you -what kinds of questions did you or would you ask to figure out whether somebody would be good at this.

My philosophy is to always hire the most talented people. Good people find a way to succeed even if to do so they have to change the organization they are in. Good people make intractable problems merely challenging, and they make challenging problems interesting.

One of the most interesting pieces of my managerial wisdom I got fromSteven Boies back at Watson. He said that the most powerful determiner of success in research is tolerance for ambiguity. That really stuck with me. I definitely look for that in people I hire.

So I got to manage, for the last eight years of my IBM career, a very small group of really good people doing basic research in HCI.

I identified more with the technical role so I stepped down. I stayed a manager, though, until 1994 when I resigned from IBM.

I was also interested in learning and information design for new users. I did that work more in the context of office systems and more general purpose systems; PC applications and so forth.

Our biggest impediment was getting a personnel accommodation. When she was hired in 1982, she joined a different group from me. We were dating pretty much from the day she was hired, but that was not an issue since we were both non-managers and in distinct groups. But in 1984, when I became the manager of the whole user interface area, she in effect reported to her husband, because we had been married in ’83. So we established a sort of non-linear reporting structure where she went directly to my manager for personnel issues. I guess this kind of thing is more common now with so many couples meeting at work, and working together.

My technical career at Watson was academically-oriented. To the extent, I contributed to the company’s business interests, it was through management and through indirect technical influences. For example, I remember when I first published a paper on the minimalist information design model. The next morning I had calls from two IBM product development labs. That led to consulting interactions, and in one case to a joint study. But – oddly in a sense – those relationships with IBM product groups were mediated, indeed they were enabled by publishing in the open scientific literature!

When I managed the User Interface Institute, we got people on 1 or 2-year temporary assignments from the IBM development labs to visit Watson as Fellows. This was a very nice way to influence development groups. When these folks went back to IBM development, they knew our work inside-out.

As time went forward, one thing that happened in IBM, was that we used IBM internal stuff not really less and less, but just less exclusively. I remember my bouts of Mac envy in the early 80s. I was one of the few people who had a Mac because I studied new user problems and I didn’t want to just study PC applications so I had Apple equipment too but basically no one in IBM used a Mac in those days.

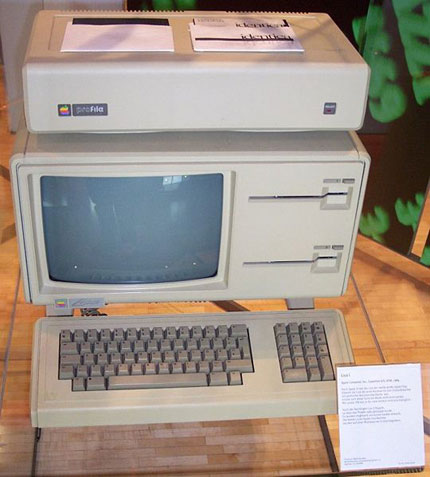

I knew Larry Tesler from when he was doing the Lisa. I published a paper called LisaLearning in which I critiqued the Lisa training and user interface as far from a design panacea. My point was not that it was a bad system, but that it was so innovative that it was scientifically important to thoroughly and empirically deconstruct it – which I think Larry appreciates. Larry has an argument that I should have studied people who knew LESS about computing and information, that more naïve people could learn the Lisa better than more sophisticated people. I find that argument a bit strained.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

Alan Blackwell has recently written a paper on metaphors that appeared in ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI). He was talking about the emergence of the idea in HCI, and of course Lisa is one of the early desktop interfaces in a commercial system. He interviewed Larry and me as background for that, and inadvertently stoked up this little skirmish again.

In ’94 I left IBM. I left because we got the offer from Virginia Tech. It was one of these ‘one faculty for the price of two’ deals. We thought well, there aren’t going to be a lot of offers like this where we’re both going to get a regular faculty position at a school with outstanding strengths in HCI, and this seems like the right time to leave, so let’s do it.

After having gone to IBM for a year and stayed for 18, I left. I was stunned that I ever did it, because I had been there long enough finally to think I was never going to leave but looking back, I’m really glad we did leave because the Watson Center, after that period of time, almost right at that time, changed dramatically.

It’s not so much for the better or for the worse; the way it changed, is it got much better, more effectively, more closely integrated into product. So now the normal way that a project is structured there, there’s funding from a product, there’s a plan to integrate the work with the product, there’s guidance from product organization.

I think IBM was never as ineffective, say, as Xerox Park at impacting the real products of IBM but after my time in IBM – it was coincidence – they reorganized to become much more effective, and I think they have become much more effective.

The way I reconstruct this looking back, is that if we had stayed, it would have been a new job anyway, a new IBM that was reinventing itself, so we may as well just get a new job.

When you go to academics, you become an intellectual entrepreneur. At IBM, if I had an idea and I wanted to pursue it, I just had to talk to one guy; my manager. If I want to do something as a professor, I have to write grants, pitch ideas to potential partner organizations, recruit and train students, and all the other stuff we do here – like teach! It’s much more cumbersome; it’s much more slow but I was older when I started this, so it’s fine for me.

When you’re younger, you want to strike fast when you have an idea, you want to act on it immediately. It’s certainly better to be in industry where they have resources within the organization to pursue their own venture activities.

Did Virginia Tech already have a department? What department did they put you in?

It may also seem odd that a university would hire someone who has never been a professor at all to be a full professor and a department head – in charge of the safety and security of discipline’s worth of students and faculty members.

I was already 44 when I started my college career, and with respect to research I was very well known. So, Virginia Tech wanted to bring me in to lead their HCI area, and it is hard for a university to bring people in at senior levels without some sort of extraordinary argument. In my case, it was the “outside head” argument. The Computer Science department went to their dean and said we need a new leader; we have to go outside the university to find a new leader. They got me.

Virginia Tech was already on the map for HCI. So, when Mary Beth and I went there, for an academic group, we had a pretty big group. And over the years, we hired a lot of people – Doug Bowman, Scott McCrickard, Manuel Perez, Chris North, Deborah Tatar, Steve Harrison, Andrea Kavanaugh. And after I left, they hired more! They have maybe ten people.

In 1996, we formed a university-wide Center for Human Computer Interaction at Virginia Tech and to help to bring people together, and also get other people – like people from the education and psychology departments; sociology, electrical engineering; to get them involved too.

In 2003, Virginia Tech decided to move its Computer Science Department into the College of Engineering. Prior to that time – and during the whole time that I had been Department Head, they were in the College of Arts and Science. We had proposed to the university to form our own College. We wanted to form a college of computing and information – what is sometimes called an i-school.

Historically, computer science departments either grew out of math departments, in which case they ended up in the college of arts and science, or they grew out of Electrical Engineering departments, in which case they ended up in the college of engineering.

Virginia Tech was a math-based department. We were in this college of arts and science. Universities are very futile and unbelievably living out of date a couple of centuries ago. If you are in this college of arts and science, it’s a real resource mess. Our department was always trying to deal with this and it was a struggle the whole time I was there.

Nevertheless, it was not really good for me personally. Although I can live with computer scientists, I am not a computer scientist. I am really a psychologist. I did not want to have to put up with the hassle of dealing with learning to live in the engineering college of Virginia Tech.

To me it felt a lot like the move 10 years before from IBM. Virginia Tech was changing, and even if I stayed I would have had to readjust. Thus, the costs of moving were reduced.

It just so happened, much as it did ten years before, that that year at a conference, I met a guy from Penn State. They had made me an offer the year before and I had turned them down. I said I am interested now. So they came back and here I am.

We also have people interested in organizational issues in systems; how organizations change or government policy in the information technology (IT) sector or law. We actually have a lawyer as one of our faculty; law in IT or IT economics; we have two economists on the faculty.

We have a sociologist. I really like the fact that it’s under one roof that I have all this mixed bag of IT people with a broad range of perspectives.

There’s a rough side to interdisciplinary – maybe you already know this – everybody disagrees about everything – they all came from a different place, they’re trained in a different way; they have different values and so forth, so it’s not like it’s living in heaven. But it is very interesting. It’s very rich. And it’s not so narrow and alien the way it would be, I believe, if I had gone into that engineering college with my colleagues.

I think our programs tend to be flexible and individualized. Students can take a lot of initiative in pursuing skills and concepts they value. In computer science there is a mentality – I call it the interchangeable part mentality: Computer scientist, especially at the bachelor’s and masters’ levels, should all be the same – the same skills, the same courses.

There are several examples of it and I think there may be more coming. To me it is a good deal for HCI.

One, is when I went to Virginia Tech, they had this project starting. It just happened to be starting the year we got there, called the Blacksburg Electronic Village. It was an experiment in community networks. They didn’t invent community networks but they produced one of the ones that’s one of the best known ones.

I got involved in computing in the home, let’s say, or in the community – civic computing. I’m still very interested in that and I am still pursuing it.

Now the frontier in that area is ubiquitous computing so it’s community networking, infrastructures implemented using broadband wireless. So that’s something that fascinates me and interests me.

I like the idea of more closely integrating information services with ordinary life and asking how can this empower not just our ability to shop but our ability to connect with other people and maybe even do worthwhile things in our neighborhood.

So that’s one answer.

The second thing that really excites me, is, oddly enough, teaching. Of course when I went into the university, I had to teach. Teaching was part of my responsibility. I have really gotten interested in teaching. I’ve made a teacher course in usability engineering that has basically been an experiment that’s been going on for seven or eight years now.

I’m very interested in new kinds of teaching materials and teaching activities; injecting different kinds of project work and case study analysis and different kinds of techniques to learning usability engineering.

I see both of those things I just mentioned, as technical projects almost without end because I don’t think there’s a question I’m trying to answer, rather, it’s direction I’m going, and I don’t think there is a final goal because I don’t think there’s a limit to what we could do.

Finally, my third answer would be I am feeling open to new areas and questions. I was always a very focused researcher, at least in my own mind. But I am 56, and I have enough success in life up to now so that I don’t feel like I must stay on the straight and narrow.

I have enjoyed letting my students take more initiative in determining what we investigate. In a couple cases, this has been extremely rewarding – students have brought me into new problem areas I would most likely not have gotten into on my own. I really enjoy letting my students drive, if you know what I mean.

I have some really good students. They’ve got really good ideas. They’re taking me to some interesting places.

For example, one of them is interested in how information technology can evoke and sustain creativity for people working collaboratively. That’s an area I can honestly say, pretty surely, I would not be working in if I hadn’t had this student.

It’s fascinating to hear how all the work you did in different fields ended up creating a straight line although who would have thunk it in the beginning.

© 2020 Adlin Inc. All Rights Reserved.

© 2020 Adlin Inc. All Rights Reserved.