Mark Hurst started his user experience career in, well, in kindergarten really. And it was because of a Marine. Later, he was all about games, and even created a non-computer-based, multiple-player game that went viral in his high school. He fed his inner geek with lots of coding, went to MIT, and did a Master’s project that ended up saving a real company more than a million bucks (did YOUR Master’s project do that? ‘Cause mine sure didn’t.) Several adventures later (including a stint working for Seth Godin), he partnered up with Phil Terry to create Creative Good and, later, the coolest conference in the whole wide world: Good Experience Live. Now his mission is to get the weight of the technical world off our backs before it breaks us…one overstuffed, unmanageable email inbox at a time. He’s totally right: bits, my friends, are heavy.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW

One of the coolest things – this was another formative moment – was when I first wrote a program on the TI 994A. I realized by typing in words, I could make something happen. I could say ‘print,’ and then in quotes I could say ‘hello,’ and it would follow that instruction. I thought that was amazing. Because up to that point, if I wrote words, they would sit on the paper and do nothing. But here was a way something would happen. I could make something happen just through the power of words.

A few years ago – in the Good Experience Newsletter – I wrote a column called The Most Important User Experience Method. What do you think it was? Was it site maps or card sorting or ethnographic research? No, no and no. The most important user experience method, in my opinion, is to change the organization.

AN INTERVIEW WITH MARK HURST

Conducted by Tamara Adlin on August 7, 2008 08:32 AM

Should we talk about a super-cool history in user experience, or…Shall we play a game?

He’s worked since the birth of the web to make internet technology easier to use. In 2002 he was named one of the most 1,000 most creative individuals in the United States by Richard Saul Wurman.

InfoWorld Magazine also named Mark the Netrepreneur of the year – I don’t even know how to pronounce that – in 1999. He foundedCreative Good in 1997; Creative Good is the world’s first user experience consulting firm. He runs it with Phil Terry (read my interview with Phil), in New York City.

Mark is the founder and host of the Good Experience Live (GEL) Conference, which will ruin all other conference experiences for you (in the best possible way).

What’s something that fascinated and interested you early in life? It doesn’t have to be work related.[/qfm]

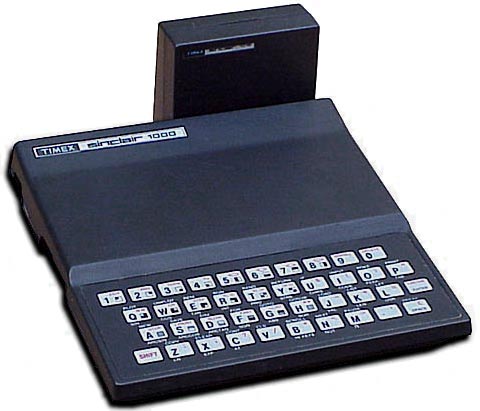

As I remember it, a uniformed Marine brought in a computer, sat it down on a table in the class, and asked everybody to put a finger on the screen, to see if it would put a block under our finger.

The computer was running a very simple program, although at the time it was probably pretty snazzy, given the standard computing power back then. It was a simple program of randomizing colored shapes; block – squares and rectangles of colored pixels all around the screen. They would refresh every few seconds.

I didn’t know anything about computers, so, as far as I was concerned, it was some sort of magic device that was reading where my finger might be.

I remember that moment because it was this very exciting moment that I knew I was seeing and experiencing something I was going to be interested in for a long time. It was just one of those – it was an epiphany.

From then on, I was aware as much as a kindergartener could be aware – I remember being interested every time I saw a computer or a digital device of some sort from that point. I was always interested to try it out.

Source: oldcomputers.net

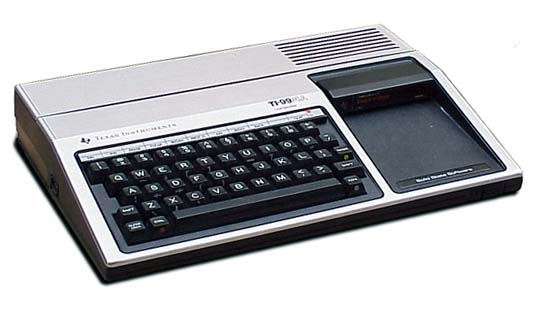

Shortly after that my parents got us a TI 994A. I remember that very well. That was the first computer I did some programming on. It was in basic, of course. That was what most of the personal computers and programming were.

Source: oldcomputers.net

I was intrigued enough to learn the basics. I’ll say that much.

One of the coolest things – this was another formative moment – was when I first wrote a program on the TI 994A. I realized by typing in words, I could make something happen.

I could say ‘print,’ and then in quotes I could say ‘hello,’ and it would follow that instruction. I thought that was amazing. Because up to that point, if I wrote words, they would sit on the paper and do nothing. But here was a way something would happen. I could make something happen just through the power of words.

At the same time, I was experiencing every video game I could get my hands on. That was much more important to me than programming.

I was really interested in what Matthew Broderick was doing when he put his phone down. Did you ever see that movie?

I was really intrigued by that and I heard about games that were being played from computer to computer over a modem. That was really interesting to me.

The only other way to play head to head on a digital game was to bring friends over. We did that a lot. But imagine if you could tap into a much greater pool of computer users who didn’t live within a couple of blocks of you. You could be playing games all the time.

I was really interested in figuring out how to create a multi-player game. There was just one small problem: we had not yet bought a modem for our computer.

It was over New Year’s break from school. I was sitting around and said I have to get a multi-player game going. How do I do it. I figured out a way to simulate a computer — I should say I found a way to simulate a multi-player online game without the use of any computers.

I launched this game at my high school in 1989 and within three months, 10% of the school was playing this game. It made the school newspaper. A couple of years later I actually patented the idea for this game and that’s as far as it went.

But I was really intrigued by this idea of playing a game with many other players online, even if I didn’t have a modem at the time.

All of this was happening in peoples’ private time and based on their fascination with it.

That was a very early stage field at that time. I didn’t end up doing a lot of interface design but I did do some work at the Media Lab. I came to the Media Lab at a good time, which was right when Mosaic was coming out andJava – and for the real veterans, Hot Java – people remember what that was – it was coming out.

I could just feel it in my bones; that this was the moment when the internet, which up to that point had mostly been ASCII- based, for hobbyists and geeks – was really going to take off in the form of the web.

That was a wakeup call for me; that better interface design can translate to business performance in some way. That was another inkling that something big was going on that I might be able to help with.

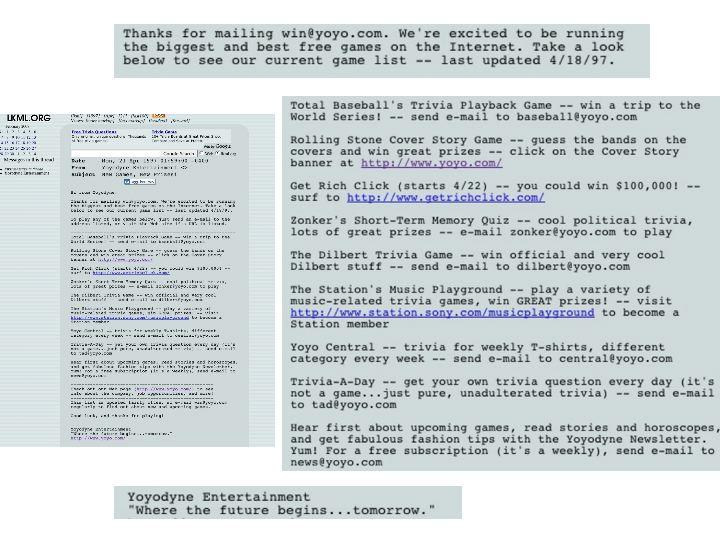

After I graduated, I went to work for Seth Godin, who was just starting an online gaming company called Yoyodyne. Let me tell you; if there was any company that was perfect for me, given my interests at that time, it was an online gaming company.

He needed somebody to head up game design.

This was early days. So the games were run over email and not via the fancy websites we have today. Remember, a lot of people were using AOL andProdigy and CompuServe. The one thing everybody could agree on was the email protocol.

If you really wanted to reach a mass audience, you went to email. So what kind of games could you run over email. They had to be turn-based; not real time, and, probably better if they are text-based.

An obvious conclusion was to run trivia games. That’s what we did. We ran trivia games. When I began designing these trivia games, I thought about what was a good model of a respected, successful trivia game.

Source (created from): lkml.org

You tell me, Tamara; you’re there in 1995, you’re trying to design a trivia game; who do you learn from? Who do you look to?

How about Jeopardy?

They do it in part by making sure that their questions are double fact-checked. They never make a mistake on Jeopardy – or almost never. They are very meticulous about the writing of their questions. They are challenging questions and it’s fun to play along. If you get it, that’s great. If you don’t, then maybe you learn something.

That’s what I began doing; not an exact match of Jeopardy, but with those patterns in mind, I began writing these games.

Until one day, we signed a contract for a game with a sponsor. We did not have very much time to get this game out the door. We had to produce it very quickly. I didn’t have time to sit down and carefully write these questions or outsource them to get them written very nicely.

We just put together a bunch of throwaway questions, like “what’s the capital of California?” – not completely easy questions but questions you probably either know the answer to or you can look them up pretty easily; nothing too challenging.

We started writing that game and what we found immediately was many more people were playing that game than the previous games.

That was a really interesting thing. Here’s a game where the questions are so easy that some significant percentage of the people were getting every single question right, every round.

We had a huge tie for first place. It was much more popular than the games where we had spent more time crafting higher quality questions. That was a real head-scratcher at the time.

Now it’s second nature, it’s so obvious. But I really had to think about it, and finally the insight came to me. People were playing these trivia games for a certain benefit, which was to get some positive reinforcement that they are in first place and they got the question right.

All of them were being built by the people you just described, Tamara – which is programmers who had an interest in design. The programmers, of course, were all creating these sites for who? For programmers. Those were the people they knew best; themselves.

So thousands and thousands of sites were being created that were impossible to use.

These sites being built by companies that increasingly had some stake in the game. They needed to make money from these sites. It was their online channel they were experimenting with.

Then we got to the late ‘90s and they were pumping untold amounts of money in these websites and they were really hard to use.

As early as ’96, I could see the writing on the wall, that this was a major opportunity to be a consultant; to advise these companies how to think more from the perspective of their users instead of their programmers to vastly increase the amount of business they were doing online.

That’s when I left Yoyodyne and started Creative Good in ’97.

It was in that state, surviving on tuna and spaghetti, that I got an email one day from Phil Terry [read Phil’s interview]; this guy who was at McKinsey, asking if I would come by and give a talk to his group. I think he had seen me written up somewhere or a notice of a talk I had given in New York. He asked me to come by.

I thought well, great; I’ll do anything to try to pay the rent next month. So I went in and gave a talk to his group. One thing led to another. We found out pretty quickly that we had some of the same ideas about the internet.

We were friends first for a few months – and got on really well. One day I just said I think we’d be good partners if you would come and join me at Creative Good. We both laughed; that would be funny. Then the next day he called me and said, ‘I think I’d like to take you up on your offer.’

One of the biggest boosts was when I teamed up with a friend of mine,Robert Seidman downloadable report that evaluated the user experience of several top sites. These days, you can sneeze and get 10 of those – finding them online.

But at that time, nobody was really thinking about this, or I should say very few people were thinking about it. It was still a rarity. When we came out with this report that was evaluating the user experience, people bought it. We were able to sell it for over $1,000 a piece.

One of the buyers of that report was Travelocity. They liked the report enough that they then brought me down to consult to them in person. That led to a long-standing relationship with Travelocity that we still have today.

There were a couple of small e-commerce companies that hired me. I was barely surviving but I survived long enough to meet Phil and bring him on board.

That’s when everything really changed.

That’s tricky. It’s tricky to message these kinds of services.

One way is to identify what a client thinks they want. You go to the client, promise that, and deliver that.

For example, a lot of clients right now think they want Web 2.0, social networking and Ajax. I’m just thinking of buzzwords.

So you could go in and bloviate about buzzwords for six hours or bring in a small army of people to bloviate individually; people in various departments. You can get a nice big fat check.

You didn’t actually generate any value but you gave the client what they thought they wanted, so they paid you.

But if you are an opportunist, you can make a lot of money surfing one wave to another.

The other way of doing consulting is the harder road, and that is to give clients what they actually need.

What clients need is to change, to improve. How do you drive a change?

A few years ago – in the Good Experience Newsletter – I wrote a column called The Most Important User Experience Method. What do you think it was? Was it site maps or cart sorting or ethnographic research? No, no and no. The most important user experience method, in my opinion, is to change the organization.

That first step is painful. That can make it a lot harder to sell work. This is just what we do; this is how we do work. I don’t know how we could legitimately do our consulting any other way.

You guys have a couple of significant differences, at least what I think as significant. One is that you do what people compare to standard usability testing, but your methods are slightly different, and you insist on always having honchos there to watch.

That’s a really important distinction that could seem subtle to some people but I want you to talk about why you did that.

We can’t simply go and deliver a report that says here’s what you need to go that’s going to improve this interface. Maybe I thought that early on in Creative Good, but that was a naive position.

We’ve generated a lot of change. Not to bang our drum too much, but if people are wondering what kind of change I am talking about, just go to thecase studies page on our website.

You can see the changes we’ve measured. These are significant changes; doubling metrics in some cases.

So how do we generate (sometimes massive) change in customer experience of these sites? We do that by pinning the entire project on the one constituency that stakeholders WILL listen to. That’s the customer.

The consultant doesn’t need to do anything special; just point it out.

As the case may be, you either bring stakeholders into the facility or you bring a camera and do some very good editing afterwards. But in both cases, the goal is to illuminate the truth about the customer experience and nothing else.

That’s where my segue is. The thing that really rocks my world about the Gel conference is that it’s not about the standard presentations.

I want you to talk about why you did that, what your thoughts were, how you built it, and how you got the courage to build something that was completely different.

Creative Good had a difficult time, like a lot of companies did, in 2001 when we laid off almost the entire company and were not doing so well.

I took some time off because I was in need of a sabbatical. When I came back from driving around the country for a few months, I had this germ of an idea, that I wanted to start a conference that was not about customer experience and business, which I knew would remain the consulting focus.

But I wanted a conference that was about good experience. Customer experience is important. I think it’s a good thing to help out companies be more effective and efficient in what they do. But really, customer experience work or user experience work, is a small subset of this much larger, much more diverse and interesting world of thought, ideas and people that I call “good experience.”

Again, business is part of it but so is art and so is urban design and so is performance and so is writing. There are any number of ways or places to find good experience in this world.

My idea behind Gel coming back from the road trip was look; if we can get people together who are passionate about good experience – no matter what their job is – then they’ll be able to take those patterns and those ideas back to whatever they do in their work or in their lives.

Of course I was hoping the user experience community would turn out because they would probably understand it immediately, better than most. I was surprised to see that a lot of people outside the user experience world started coming to the events also.

Now we’ve run the event five times in New York; we did one in Europe and they happen every year in the Spring in New York [learn more about the GEL conference].

After running it for several years, we now have a group that comes back year after year. They come from all over the world and from all different kinds of jobs and organizations – interesting people who are interested in this topic. It’s very diverse.

I try to get a speaker list that reflects the diversity. We always have one or two business oriented speakers or technology oriented speakers but the majority of people do not speak directly to usability or user experience. To me, that’s refreshing.

Unfortunately it’s hard to explain to your boss why they should spend money to send you to GEL.

One that I did was with Cliff Nass [read Cliff’s interview]. One of the things he said was all of the answers are really out there – it’s just that most people are looking in the wrong literature. What he did, of course, was a lot of classic sociological experiments where you replace the person with a computer, in many cases, to look at how people behave with respect to computers in terms of politeness and reporting on performance and things.

I think you’re doing something similar in that it’s not necessarily the literature that has the answers but it’s the artists; the other creative people who have looked for ways to communicate in new ways or get messages across – anything like that.

At GEL we turn that on its head, and, rather than specialize in one area, we’re going to generalize to areas you know nothing about or have no professional connection to, for the most part. We’re going to challenge you to find the connections, in the same way you are finding connections between your diverse interviews right now.

If you can find those patterns, they are so much more valuable than getting a tutorial on something you could probably read up on in a few minutes.

, which I read and loved. I want to ask you about it in terms of being brave enough to write something that was really so basic.

It’s about basic ways of interacting with computers, and inspiration. What inspired you to take the time and risk to do that?

I didn’t think anything of it; it’s just how I used the computer. He said, ‘no; that’s really unusual. Can you teach that to me?’ So I taught him and we eventually taught the company.

So for years I’ve been meaning to put it in book form so I could share it with the world. I think it’s – as you say – a very simple book. It’s not a book about Web 2.0 or the coming technology trends, although they are referenced. I think what people increasingly are going to need, which almost no one has today, are some basic skills in how to live in an environment that is saturated with information.

Email is one of the sources of a lot of anxiety and stress today. One of the major chapters is on email. But the set of skills, which collectively I call Bit Literacy, are not just about emails; they’re about managing To Do’s and a media diet and learning how to organize your files, name them properly; where to store your bookmarks – all kinds of information/management skills that people need today.

In a few years, they are really going to be in trouble if they don’t learn these basic skills.

These are techies, newbies, young people, old people. I think part of the reason there’s such a diversity of positive response is I didn’t intend for it to be a restrictive method that is set in stone. Rather, what it is is just a few basic skills from which you can then create your own method; your own strategies for dealing with information.

Rather than being a straightjacket of clockwork steps to follow, it becomes a way for you to liberate yourself from the stress and anxiety of the technology.

And we know from usability tests that people congratulate themselves on handling things that were incredibly difficult. So a person can go through a usability test experience, have a horrible time and at the end say that wasn’t so bad, congratulating themselves on having mastered it.

Perhaps the people who refuse to review it are just in some ways trying to build their own reputation as a reviewer on having mastered complexity. So maybe it makes sense they’re not interested in it.

The responses you are getting to the book have to be largely positive.

I don’t think I’ve heard from anyone who said I tried it and it was bad or did nothing for them.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are a number of people – if you just go to bitliteracy.com and click on the endorsements link, there are a bunch of reader comments saying the book has changed their lives. That’s another common refrain.

I’m glad to hear it. I know that I cannot survive unless I practice these skills. And it is a practice. It does require some discipline. But if I fall off the wagon, so to speak, for a couple of days … I actually don’t know how anybody gets anything done anymore unless they have some semblance of a strategy for dealing because a couple of days off, and I’m dead in the water.

Some people go their whole careers without figuring out how to ever manage their bits. It’s amazing.

The world has changed in the last 10 years. Computers are no longer this thing off to the side that we go and sit down with once in a while. In fact it’s not about computers at all; it’s about bits. The bits are what’s important.

The device itself is becoming less important whereas the management of the bits; that is to say the messages and all the other streams of information – managing the bits – that’s what’s important.

That is a complete change from where people were 20 years ago. The skills of computer literacy are where we stopped. We taught people how to use the mouse. If they are lucky they might take a class on Excel or Word but that’s all the workforce has been trained to do, and the world has changed.

People are beginning – even the ones who know how to use Excel – imagine this – you’re an Excel expert and you still can’t get your work done because you’re drowning in emails and To Do’s and all these other information streams, and you’re not sure what to do.

There is this problem no one has really identified or talked about.

That, by the way, is the hook of the book. There’s a chapter of creating bits when I talk about leading with the hook, which is the main idea. Bit literacy starts with the hook; that is the hook of the entire book – the entire idea – and I’m glad I state it up front because if there is a competing theory that is well thought out and in some cases well written, it is the opposite of that hook, which is a lot of people, especially some tech experts, believe that bits are not heavy.

That’s the philosophical battle that’s coming between people who believe in the weight and disbelieve the weight.

I think we all live in houses stacked with newspapers and paper bags.

There’s a book that recently came out called A Perfect Mess, which praises people for being cluttered in their life. So now there are books and technology luminaries and companies supporting the effort out there.

They are all behind this idea that users do not need to get organized but rather let the bits pile up and just rely on the technology to take care of them. I couldn’t disagree more with that.

People in ecommerce are moving away from building and maintaining their own retail technologies, and outsourcing this stuff. I always say that if your core business is selling socks, why do you have a web team?

I think there’s something similar in that—that people are finally realizing that you don’t have to have all l the technology or all the know-how in-house in order to get the benefits of this technology.

I don’t know what the connection is but something is –

That’s a good way to garner press attention by staying on the leading edge but I believe something different which is that the user should be in charge and that the technology should be subservient to the users.

In that system, the users have to take responsibility.

And you need to take responsibility in a way that you haven’t in the past. Boy, that’s a tough message to sell people.

The hedgehog is maybe not as sexy as the fox but is dependable, focused and reliable on one idea. So Phil and I knew almost from the very beginning that he and I both are hedgehogs. You won’t see us talking up the latest buzzword or trend.

We are interested in improving the customer experience and improving the experience that people have with technology.

How many consulting firms that people work with actually make it really enjoyable to consume consulting services.

Thank you for taking all this time today.

© 2020 Adlin Inc. All Rights Reserved.

© 2020 Adlin Inc. All Rights Reserved.