What do Aristotelian poetics have to do with human-computer interaction? Quite a bit, if you think about it like Brenda Laurel does. From an early interest in interactive theatre and interactive fiction, through falling in love with computer graphics and learning to code, and a long career designing computer games, Brenda has kept the cultural aspects of HCI at the forefront of her work. In this interview she talks about her work designing games for girls, and about working with others who inspired her (including Timothy Leary).

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW

I was pretty fed up by that point by seeing how the gaming world was very gendered. I had some pretty deep research on how girls play. I wasn’t going to accept the street wisdom that girls just didn’t play computer games period, end of story. That was not something that made any sense to me since I was a game player. We did a lot of work with thousands of kids and tried to understand the kinds of play that attracted girls; not just computer play, but play period. I think if we’d asked what kind of computer games girls would like, we wouldn’t have gotten an interesting answer. So we asked deeper questions, like how does play differ according to gender in the age group we were looking at.

I bring with me a couple of observations about what it means to be a good designer that have almost nothing to do with skill. One is that design is activism. Our engagement is with popular culture, it’s with global culture. We’re not so much about sitting around understanding ourselves or extruding our interior experience like a fine artist might be, but rather we’re about engaging and shaping the world. Design does that, and is incredibly powerful in that regard. Since we have that kind of power we need to understand what the tools are to engage that way, and we need to frame ourselves in relation to the world, as an agent, as an activist, as a source of power and change.

AN INTERVIEW WITH BRENDA LAUREL

Conducted by Tamara Adlin on June 5, 2007 11:32 PM

Want to see what passionate thinking looks like? Peek inside a brain filled with theatre, invention, games for girls, and design-as-activism.

She is currently the chair of the new graduate program in design atCalifornia College of the Arts Her career in human computer interaction spans over 25 years, which is one of the reasons I’m so excited about talking to her today.

Her book, Computers as Theatre, was one of the very first books I encountered when I started getting interested in this field. She’s also the editor of The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design

.

Hello! Thank you for finding the time for this.

Interactive theatre is where you have a rough scenario or pieces of script with improvisational interludes. It’s a lot like Commedia dell’arte in that regard. The scenario basically outlines what the plot elements are, but audience members’ responses direct improvisation on the part of the actors. In some cases, audience members become included in the actions, but that typically doesn’t work so well because people got embarrassed when they got called upon to play parts.

Also in the tradition of Commedia, the script that got played in any given town might be responsive to what was going on in the town at the time, so there was kind of a responsiveness to current events and locations involved in the tradition. We tried to maintain that in the work that we did.

So in ’79 I came out to the golden west from Ohio and started working at Atari, and got back to my dissertation when I realized that I was almost out of time.

By then I had become really interested in computer games and interactive fiction. I conceived the idea of figuring out what we could do with some of the principles of Aristotelian poetics in building smarter game systems. The goal was a system that could generate next actions, or conditions for next actions, that would lead to dramatically satisfying experiences.

I saw NASA images showing up on a screen in his lab. I sort of fell to my knees and said, “Oh my God, whatever this is I want a piece of it.” About a year later he quit his job, and he and his colleague John Powers founded Cybervision because some guy had shown up with the ability to do interactive stuff via the television. Since Joe knew of my interest in theatre, he asked me if I would be interested in designing some interactive fairy tales.

It all seemed very smooth at the time. The only hitch was that I had to learn how to program.

I found myself doing things like reinventing cell animation because I was so ignorant about how animation worked. I was programming lip synching and stuff in an environment of rudimentary technology. We’re talking 2k of RAM here! It was interesting.

Typically what would happen is that I would want something to happen and I would say, “Boys, you need to write me a subroutine,” and they’d go in the back room, code up something in assembly language, then let me call it in ajump out, so I didn’t have to do much heavy lifting in that regard.

Plus, I had studied stagecraft and set design and things like that, that were moderately technical. It didn’t seem like a big leap.

When I moved to Atari, I actually got into a management job, originally managing the educational software effort. I think I was the first software producer-type person for the Atari 400-800 series. We were trying to think what we could do with that machine in the realm of education.

Then my group got bigger and we started doing all of the software producing for that machine, which immediately took us into the realm of translating some of the games that had existed on the Atari console into the 400-800 environment, and developing new games for that environment because it had different capabilities.

After about two years of that, I hit the wall. Atari was hitting the wall at the same time. I realized I wasn’t getting what I needed intellectually and creatively. It so happened that Alan Kay had just been hired as the head of Atari Research. I had had several conversations with him. That was when ideas for my dissertation started forming, because I was talking to this brilliant research guy.

Alan brought in a bunch of people from MIT’s Architecture Machine Group (which was the precursor to the MIT Media Lab) to work in the Atari lab – so I had the opportunity to be around people who had already been thinking pretty deeply about interaction and got a lot of support in following the holy grail of the idea of this more intelligent game system.

As it turned out, the way I approached it in my dissertation wasn’t particularly feasible, because in those days expert systems were all the rage, and I thought that was how we were going to go about it. This was before the monumental discovery that the most interesting character in a game was actually another human player. When that happened – it seems like Habitatfinally broke the wall down there – the whole idea of using big AI to design computer games got back-burnered, although people in the game industry continue to be very concerned about using flavors of artificial intelligence to animate machine generated characters.

I remember one time the management of Atari called the lab and wanted to know Arthur’s home number, so I got on the phone with my vocoder. Also, Arthur was British, so I had a voice like this: (emulates voice).

I gave them the number for dial-a-prayer in Boston, so if anybody ever tried to call him, they got some religion.

People in the lab were not just technical people. There was a lot of interest in character. One of my colleagues was doing facial recognition, and thinking about how to animate faces so that, for example, women in the Arab world could do business with men through a virtual persona.

We were surrounded by people who were doing very imaginative things even though they were technically skilled.

I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Well, if you use an ATM, you are experiencing human factors design.” ATMs were a brand new thing in those days.

I kept that in the back of my mind, I guess. Later at the Atari Lab, I became acquainted with Don Norman and started talking with him a lot, and wrote a paper called “Interface as Mimesis” that he published in his human-centered design book (Full title: User Centered System Design: New Perspectives on Human-Computer Interaction).

I was starting to think of UI (user interface) as an idea that’s related to poetics, and that has to do with imitation of life. Don actually mentored me through the beginning phases, I guess, of my dissertation work.

I was lucky. I got to the best guy in the field quite by accident. My life has been so wonderful with coincidences like that. I’ve had the chance to work with such terrific people all quite by accident.

When I was finished and I showed the manuscript and ideas to my editor, who was at Addison Wesley at the time, he said, “Oh man, this is really revolutionary stuff. You ought to think about turning this into a book that would explain your thinking to other people.”

So I rewrote the thing, and that’s where Computers as Theater came from. It’s what everybody does; they try to turn their dissertation into something readable by normal humans. That’s how that went down.

My editor (at Addison Wesley) was also the editor for that book, so I approached him with Computers as Theatre, and he went for it. Later on when I got back to writing books again, I started working with MIT Press. My last two books have gone through MIT Press.

It was a disturbance in the force, I think, to have that kind of person writing in the book, but I am glad it happened

I jumped to Epyx because my friend Joe was at Epyx, and was there just in time to turn the lights out. It was a pretty depressing run.

In ’89 I got involved with the Apple research people, working with Alan Kay and Rachel Strickland down in Los Angeles in the Vivarium Project.

Rachel and I were working on storytelling and narrative intelligence as a way to think about getting kids involved in programming. We were using coyote stories. It was this great experiment with Native American stories to see if kindergarten kids had the western notion of narrative already burned into their brains or not. It turned out not; that they were able – and interested – to do fairly nonlinear things with storytelling when we gave them tools.

Vivarium was a place where we could try out a bunch of ideas about engaging kids with technology. Then, after that I wandered into the human interface group proper, and got the job to do the book with them – which was really interesting for me. It was sort of like anthropology because I was really trying to channel the contents of other peoples’ brains about what was going on in the business.

After that was over and I had published Computers as Theatre, I was on the speaking circuit. I did a bunch of virtual reality work. About 1992 I met David Liddle at a conference. He hired me to come to work at Interval Research, so my life ignited again.

I got back into the place I wanted to be in a research capacity. I stayed there for the whole ride, although in ’96 my work on gender and technology got spun out into Purple Moon, which was a startup company that did games for girls.

I was pretty fed up by that point by seeing how the gaming world was very gendered. I had some pretty deep research on how girls play. I wasn’t going to accept the street wisdom that girls just didn’t play computer games period, end of story.

That was not something that made any sense to me since I was a game player. We did a lot of work with thousands of kids and tried to understand the kinds of play that attracted girls; not just computer play, but play period. I think if we’d asked what kind of computer games girls would like, we wouldn’t have gotten an interesting answer. So we asked deeper questions, like how does play differ according to gender in the age group we were looking at.

Purple Moon was the result of a lot of heavy lifting.

One major issue was that in those days the play community – the people who looked at play – were labeling constructive play as being pretty much something that boys did. They were thinking of it in terms of this box, this ship, building forts, stuff like that. It turns out that girls can engage in constructive play too, but they do it most often in the form of narrative.

That was a big key. Girls are really interested in free play, where you’re building a story, you’re trying to understand a story, you’re engaging in a story in some way.

I guess the other big finding, although there were many, was that there are biological reasons why girls are not as interested – or weren’t, in those days – in action games. In those games we were looking at side-scrollers, and it turns out there is a statistically significant gender difference in the domain of what’s called “mental rotation,” which is imagining an object in a different orientation. So if you’re looking at a side scroller but you’re playing an action game, you have to do the mental rotation of 90 degrees to see yourself as being in a first-person view with those characters.

There were a few POV (point of view) games, and not surprisingly, girls like them. Sonic the Hedgehog is one.

So this business about mental rotation and navigational styles… Girls tend to be more body-centric and interested in landmarks as a navigational tool, whereas boys are more likely to do dead reckoning and are very comfortable, say, with plan views of environments.

Those pieces of information about brain-based differences helped us to think about designing a UI that would be more attractive to girls.

That led to the observation that you can get a person – female, let’s say – to perform better at a navigational task that’s exactly the same if you frame it differently.

Say they’re trying to drive this car from here to there and you show them a map. They’ll perform better than if you tell them they are trying to get through a maze, because the way they are framing the problem psychologically allows them to tap into other skills.

Does that make sense?

That’s not huge, but it’s important. I think the social content of the Purple Moon games was the result of understanding girls at the tween age and what is nagging them; what are the issues in their lives at that age.

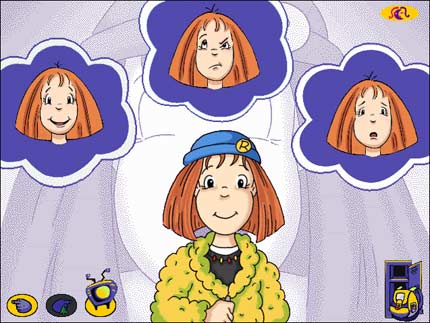

We learned a lot of things about how girls construct their identity. There are really two kinds of identity that most girls have at that age. One is social and quite concerned with relationships in the external world, and the other is very interior and tends to be more age-appropriate.

So when they’re in their social selves they’re imagining themselves to be a bit older. When they’re in their inner selves, they’re at their right age – at the same age or maybe even younger.

Different principles apply, but the same concerns are worked out in different ways in the two frames that girls tend to have as they struggle to become adults at that very difficult time of their lives.

It was an interesting ride.

We were rolling our own. We had a web presence that was very strong. In fact, we were beating Disney for about three months in terms of dwell time and hits.

But we were also making real products – CD-ROMs – that had to be manufactured, warehoused, shipped, gotten into shelves at retail, etc. Investors in the late 90’s saw in the online world a situation where none of those problems existed. You didn’t have material goods to worry about, and the valuation of a company that didn’t have material goods as part of their product line could be astronomical.

So our investors got very restless. They wanted to put their money into one of these online companies with 100x return on investment deals, like pets.com or something. They were saying, “We’re not going to mess around with you CD-ROM guys anymore.”

We were looking for investment, but right in the middle of trying to land investment with Mattel our Board quite suddenly shut us down. We managed to get ourselves sold to Mattel just to make everybody whole and pay everybody the money we owed them, and then of course Mattel acquired – in 1998, 99 and 2000 – they proceeded to acquire every single company in the space of games for girls as a defensive move to protect their property,Barbie.

It was like a snake that ate something too big. The investment they made was so huge – on the order of $700 million – to buy all those companies, that they didn’t have the money to service the brands.

So they ended up killing almost all of them except the American Girl brand, and then eventually within a year they were out of business in the interactive side. Then (CEO) Jill Barad got fired, and that was the end of the story.

At the same time, because the web was becoming so much more accessible, our mission of getting girls comfortable with technology was being accomplished by their engagement with the web, so the social need to do something targeted to females for the purposes of getting their hands on the machine was passing. The need for that kind of intervention for that reason went away. I think there is still a huge market, obviously, for girl’s and women’s games, and people keep making little runs at the fence, but as you know the game world is not particularly keen on research. They’re not asking the right questions a lot of the time.

Anyway, I went down to Art Center, helped redesign the curriculum, and got really engaged in teaching. Eventually when Andy left I became the chair of that program, and chaired it for four years.

During that time, it was rough times here (San Francisco Bay Area). It was post-bubble. My husband, who is an inventor and researcher, had a lot of trouble finding work. He had finally gotten a gig at Sun. The guy who was running the lab there was somebody we’d known from Interval, and he asked me if I wanted to work there.

I was doing two jobs at that point. I was commuting to Los Angeles every week, living in a little apartment down there to be chair of the media design program (at Art Center), then coming back up here and working the other two and a half days at Sun Labs.

Sun Labs went through a layoff, and I offered myself up because at that point I was so exhausted I didn’t think I could breathe. So they kindly laid me off and unkindly laid off my husband at the same time.

We were back at “yikes” moment. I kept teaching at Art Center and one day I just said “I can’t get on an airplane again. This is killing me. I’ve got to do something else.” The very next day I opened my email and there was a note from the then president of CCA ( California College of the Arts) saying, “We’d like somebody to come up here and start an interaction design program.”

It’s hard to find something that exists in the world that doesn’t exist in more than one media type, if you think about it.

My vision at Art Center was the same, but now I have industrial designers included in the program, and we’re able to work in 2D, 3D and 4D, so it’s a grand experiment. We’re watching this thing in the fall, but we’ve got a great crop of students coming in and I think we’re going to go to the next level in terms of design education.

I bring with me a couple of observations about what it means to be a good designer that have almost nothing to do with skill.

One is that design is activism. Our engagement is with popular culture, it’s with global culture. We’re not so much about sitting around understanding ourselves or extruding our interior experience like a fine artist might be, but rather we’re about engaging and shaping the world. Design does that, and is incredibly powerful in that regard.

Since we have that kind of power we need to understand what the tools are to engage that way, and we need to frame ourselves in relation to the world, as an agent, as an activist, as a source of power and change.

I’ve never stopped wanting to help younger people who are very bright to understand that they have power, that they can get into their power, giving them tools about strategic thinking and research and even business – intellectual property law, stuff like that – so they can enter that world not as a stoop-labor programmer or graphic designer, but as a potent force who can think large and provide vision and strategy for a company or client.

It may not be that those things show up in a particular design, but the question needs to be asked every time. I am really interested in the fact that I think we need to stand up faster, work harder, work stronger, and be more proactive about what kind of world we want to have.

I know that for artists, and I think this is true of designers as well, there is such a tendency to be self marginalizing and to say, “Oh, I’m going to stand here outside of the spectacle of the world and comment on it, throw little paper airplanes into it with messages that things are wrong.”

There is a fundamental shift we need to make. It’s easy. You just say, “No, actually, I’m not outside, I’m in the middle. I’m in the center of the world, I am the wellspring of popular culture because it’s the truth.” So often that’s really all it takes to make a talented person a powerful change agent.

It’s not interesting to me to fiddle around fussing with stylizing. Styling things – and this is a big argument in the design community world – are we stylists? No, we’re not. We’re inventors; we’re protean. I’m glad to see that CHI is driving back towards that kind of muscular thinking.

For example, the engagement CHI has now with sensors and sensor networks is very interesting to me. I don’t think we have time to fool around with menus and buttons. There’s a lot of stupid stuff that’s fundamentally wrong in the world of industrial design and interaction design that we’ve been persistently trying to make better, and we ought to just move off of it, do the next thing.

© 2020 Adlin Inc. All Rights Reserved.

© 2020 Adlin Inc. All Rights Reserved.