Aaron Marcus spent a lot of time with his nose buried in comic books and science fiction stories. When it was time to learn things, he chose to learn…everything. His history reads like a who’s who, and a where’s where, or the early days of our field. My favorite part? He went into more than one job interview saying “I don’t know why you would want to hire me.” That makes one of us.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW

I have to admit: it’s a wise newbie or youth who actually looks to some older people and says, “Oh, they might have something there; let me go ask.” A more typical opinion is, “I think I know better. This is all new. Nothing like this has ever happened before, and I have unique insight into the situation.” That may be so. But I think we can learn from our elders. Especially now that I am an elder, I naturally favor that opinion.

I’m Tamara Adlin. Today I have the honor of talking to Mr. Aaron Marcus, who is the President of Aaron Marcus and Associates, Inc., or AM+A. He was graduated with a degree in physics from Princeton, and in graphic design from Yale.

In 1967 he became the world’s first graphic designer to work full time with computer graphics at AT&T Bell Labs, where a lot of early work was done in the field of user experience.

In the early 1980s he was a staff scientist at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. He founded Aaron Marcus and Associates, and began research as a co-principal investigator of a project funded by the U.S. Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Project Agency, or DARPA.

In 1992 he received the National Computer Graphics Association’s annual award for contributions to the industry. In 2007 he was named an AIGA Fellow. In 2008 he was elected to ACM’s CHI Academy, and he serves as Editor-in-Chief Emeritus of User Experience Magazine, and is an editor of Information Design Journal.

Mr. Marcus has written over 350 articles, has published 15 books, and has lectured, tutored, and consulted internationally for 45 years.

He is a true UX Pioneer.

Welcome, and thank you, Mr. Marcus for being with me today.

I’m going to start this interview the way I’ve started all of my interviews: what is the first thing you can remember really fascinating you as a kid?

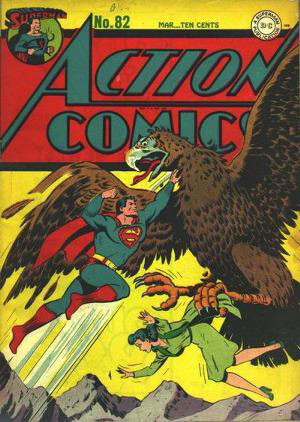

I collected myself about 18 different brands, and two of my friends and I had an agreement that we would each take a different portion of the complete comic book universe. Another of my friends actually took science fiction.

I took DC Comics and Marvel Comics, if I recall correctly.

I also made things. I guess it was an early version of the Maker phenomenon [the current interest catalyzed by 3D printers, for example], because I built pretend rocket-ship control-rooms in my basement. My late brother Stephen, friends, and I would “take trips to other planets.”…[I guess you could call it an early form of “trippin’out.”]

I think what was intriguing to me was designing the control panels: the dashboards, the displays, which I made out of junk that I found in alleyway trashcans. You know: dials and gauges and knobs and old radio parts.

I remember one of the concepts that we invented at the time was

“The Big Book of Knowledge” in which one could find the answer to any question. This concept was our version of Google in the early 1950s or late 1940s.

Little teddy bears would grow like fruit on the trees. Their heads would emerge, and when they were ripe, the full bodies would fall off, and the little teddy bears would walk around on the ground.

Tell me a little bit about your experience in school, and what you focused on when you were in elementary school and in high school.

I was always interested in science and art. I didn’t actually know very much about the word design because design was not then — and still is in many ways, not taught well, at least within the U.S. school system.

So I loved drawing and painting. I learned later as a college student about photography and calligraphy.

In grade school I was introduced to color theory. I still have the sheets of colored paper that I pasted up to demonstrate color phenomena I can’t remember which year-class it was. But because of this experience, I not only enjoyed science and mathematics classes, but I also enjoyed any creative classes of arts, crafts, and design.

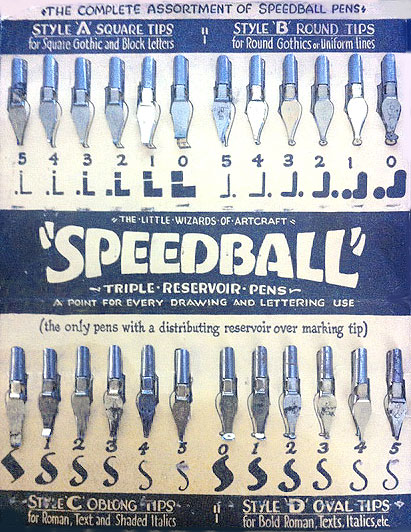

In fact, I’m just remembering now my Speedball pen set, with which I made letters and posters and practiced calligraphy in grade school, and certainly in high school.

I think I was a certified nerd early on. When I was six or seven or eight, my uncle was teaching me algebra. I thought that was kind of cool.

One of my childhood accomplishments of which I was proud, was that I had memorized the value of pi to 50 decimal places. I don’t know how many kids would want to do that, but that’s what I enjoyed doing.

I didn’t play that much baseball, and participate in other kinds of activities that more socially oriented kids would do.

In fact, just to jump ahead, it took me about 10 or 15 years after I got my professional degrees to figure out how it all fit together.

I remember in 1979, when it became clear to me. I knew I had programmed computer graphics. I was interested in graphic design, visual communication. I was teaching at University of California at Berkeley at the time. I received an invitation to address federal graphic designers at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., through colleagues of mine at the National Endowment for the Arts. They said a famous graphic designer had become ill; would I like to step in and give the presentation for this occasion? I was frightened to death, but I said, “Sure.”

Then had to figure out what on earth I was going to talk about.

I went into the ozone worrying about this pending event and thinking about it for about three days. It was somewhere around November 22, 1979.

Out of that turmoil came the realization that I could put together all of my background and interest of computers and technology; science and mathematics; philosophy and visual communication; graphic design, art, everything.

Out of that challenge came the understanding that I could apply the principles of visual communication to the emerging world of computer graphics technology. Once that pattern became clear, suddenly a lot of clouds disappeared from my thinking, and I saw the pathway forward.

But I did not see that so clearly for 10 or 15 years after finishing graduate school.

That’s when you realized that this sort of winding path was potentially making this wonderful straight line?

When I got to art school and design school as a master’s student, I already owned all the necessary tools. I just didn’t know what they were for. But I’d been collecting them and using them all my life. But I didn’t understand why.

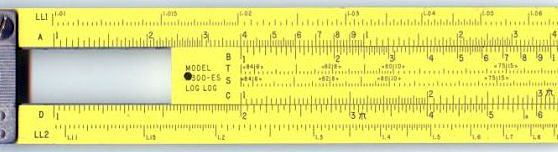

I thought it might be better if I had a liberal arts education and did not immediately have a “slide-rule education”, as I called it. I hope you know what I mean by a slide rules [The old analogue computing tool made of several pieces of wood or metal with number scales that could be used for simple computing.]

It was with some concern that I felt I would not go on to graduate school in physics and study laser technology, which is what I was drifting towards, because I was really more interested in general theory of gravitation and other topics.

I subsequently applied to several art and design schools like Cooper Union and the Art Institute in Chicago and the Rhode Island School of Design. I got into all those schools but only one school was a graduate school, one school had a graduate program, and that was Yale.

I thought well, I don’t want to go through an undergraduate education all over again. I think it’d be best if I moved forward at the graduate level. They had a special one-year program in which I was supposed to learn everything that my peers had learned in four years!

You went to Princeton, where you were thinking that you were going to move forward into lasers and physics, and did go ahead with a wonderful undergraduate liberal arts degree as well, and all of the sudden you’re talking about getting into amazing undergrad and graduate level art/design programs.

That’s not something that’s familiar to a lot of people; being fluent in highly technical, mathematical, scientific fields and being able to get into Yale Art School.

Tell me a little bit more about that.

I took printing and typography classes in my spare time in Princeton’s Visual Arts Program. I learned Italian chancery cursive handwriting, because I thought it was beautiful and interesting, and I practiced it.

I sat in on painting classes with figure painting and still-lifes. So I had some things to show.

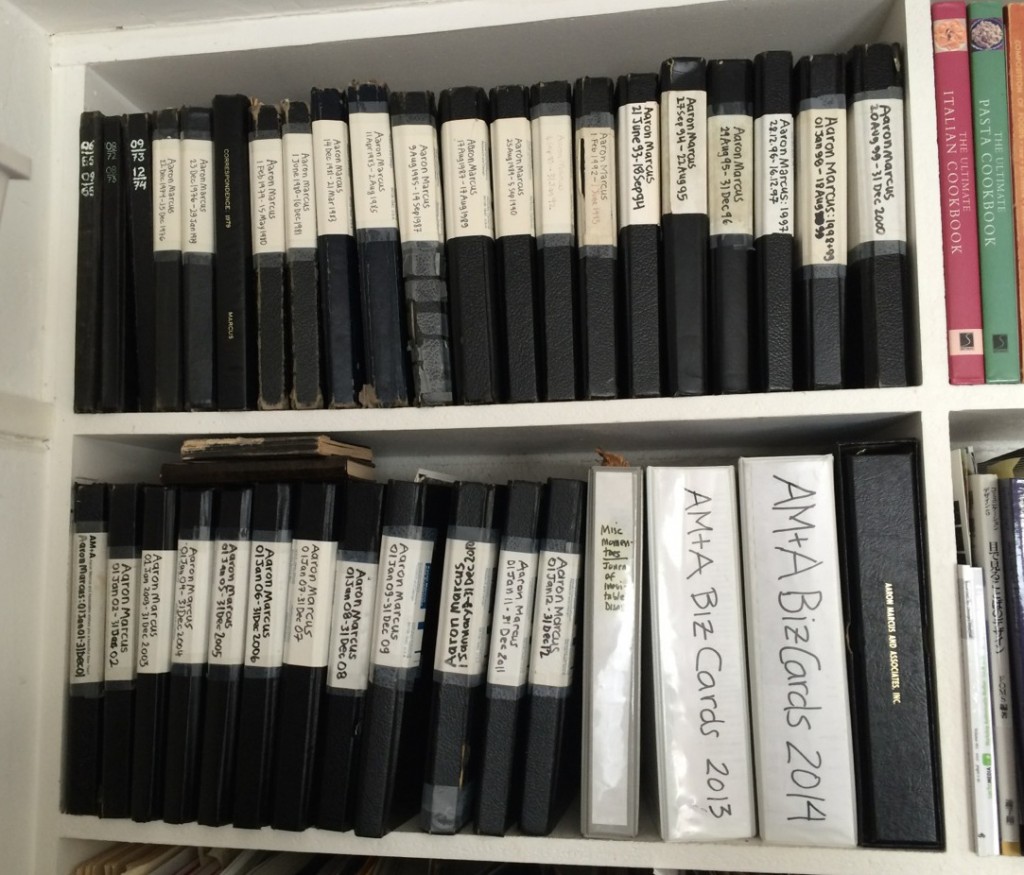

What 50 Years of Diaries Looks like.

Men At Cafe.

Figure In Coat.

Architecture.

When I first arrived in graduate art and design school and was taking design courses, I had no idea what anyone was talking about. I didn’t know what the words meant. If someone said “Oh, that works,” I would say, “What works? What is it that’s “working? What are you talking about?”

It took about a semester, half the first year, year, before I got it; I grokked it. I realized that what they were talking about was something similar to what I had done in physics labs where I tried experiments.

A lot of the work that I was doing as a graduate design student was trying things and thinking about principles that might lead one from here to there, and where to go next, and taking note of what happens

And it began to make sense to me.

So to contextualize this for everyone reading, imagine going to grad school as if you came in with the understanding of your field that you would on the first day as an undergraduate. That’s amazing that you went in so fluent in the stuff that you had studied as an undergrad, and yet so non-native in the field that you were doing advanced work in.

As I say, it all seemed a little surreal to me. But … eventually things settled down and I was learning so fast that essentially I didn’t sleep for about three years.

All during those three years, to get the first baby graphic design degree in the first year and then move onto the master’s degree for two additional years, was so exciting. Everything was so new and fresh. Whereas for my classmates, a lot of it was just more of the same with some refinement.

I can understand that. But for me, I was on another planet. It was so interesting and so much fun that it was too boring to sleep.

That’s part of the challenge I have faced personally in my career because I was never fully accepted by the design community, nor fully accepted by the computer technology community because I was always slightly different.

I considered myself a Janus figure – a doorway-figure sitting between disciplines. I could look into each of them. I could talk with all of the people. I had learned how to be them. But I was not just one of them.

It was quite frustrating at times.

I want to say, also: you said “did you consider yourself unique” in doing something. In my early years, as young people are perhaps prone to do, I did think of myself as unique in some ways but as I’ve grown older, I’ve just found myself so typical in many ways.

Growing older, having a family, having the pressures and the challenges that one has in life, I am just startled by how average and typical and ordinary my concerns and interests and directions are. So that I realize if I have what I used to think of as brilliant, new idea – I think: “Oh, there are probably nine or 900 people having the same idea right now around the earth, thanks, in part, to our means of instantaneous communication.

That realization has fueled my interest in cross-cultural communication and some of the other topics in which I’ve been interested in, like mobile persuasion design, in the last decade.

Let’s hop back to that moment in 1979. You had been finished with your undergrad degree, you were finished with both your undergrad and grad degree in graphic design. When did you finish with your degrees?

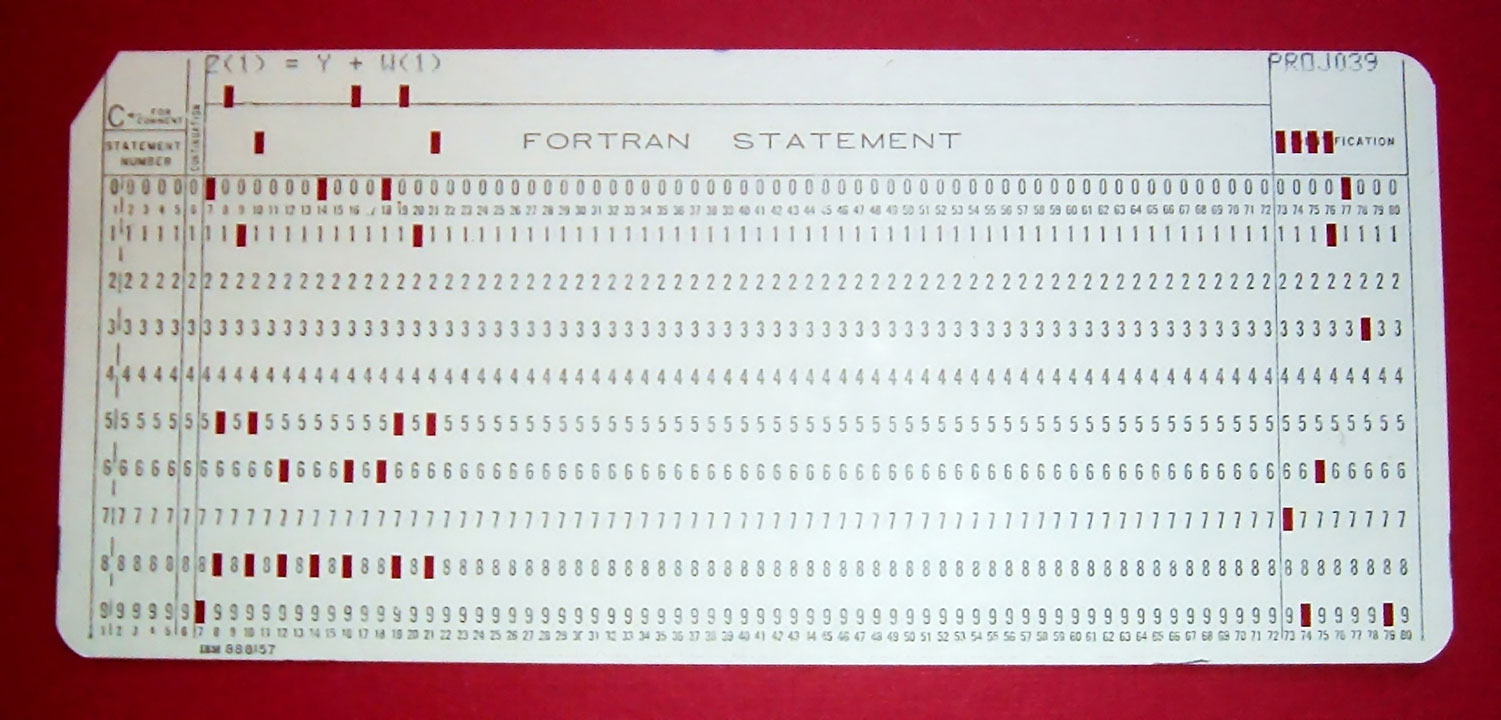

I taught myself at the computer center FORTRAN programming, a popular programming language for science and engineering. I went to this interview from AT&T Bell Labs which took place in….it must have been May of 1967. I did the sort of thing that you would tell someone never to do

I said, “I don’t know why you would want me.”

The two men turned their heads, looked at each other, smiled gently, looked back at me, and one of them said, “Well, actually we’re looking for someone exactly like you.”

I went on to work with those two guys as a summer intern at AT&T Bell Labs. I was suddenly plunked down in the most advanced computer technology on the planet.

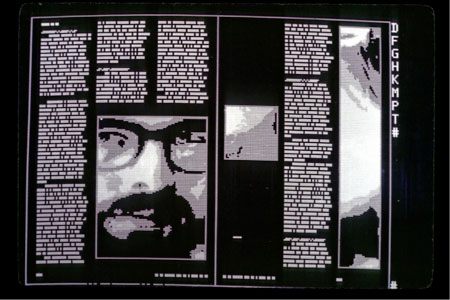

Early desktop publishing system for the ATT Picturephone. Photo by AT&T Bell Labs

Were you just over the moon inside?

There was an exhibit in New York – the Experiments in Art and Technology – which published a conference proceedings in about 1970 or ’72. It gave me at Bell Labs an opportunity to meet advanced filmmakers; Nam June Paik, one of the first and major video artists, from South Korea who was considered a national treasure of his country; Stan Brakhage, Virgil Finlay, if I remember correctly; and others.

Peter Denes was my superboss, and Michael Noll was my immediate supervisor. At that time, Michael was creating the first 3D virtual realities. Ken Knowlton was creating the first computer animations. Max Matthews, invented computer music and computer speech was around – you know the “Daisy, Daisy” song from the film 2001?

(Listen starting at 40 seconds to hear the ‘Daisy, Daisy’ song recorded as part of a 1963 Synthesized Computer Speech demonstration by Bell Laboratories. )

When I started working there as a consultant in ’69-71, it was the first time that television sets, that is, raster scan displays, had been attached to computers. It was black and white television screens, so to speak. Not cathode ray oscilloscope or CRT [cathode ray tube] screens with vectors.

So I finished that desktop publishing project and published a paper about my work, as I tried to figure out what was the future for design, in particular graphic design.

[See, Marcus, Aaron, “A Prototype Interactive Page-Design System,” Visible Language, Vol. 5, No. 3, Summer 1971, pp. 197-220.]

In fact, that was one of the first occasions in which I designed a computer-based user interface for the software that would be running on the Picturephone.

Microfilm from the collection of Aaron Marcus

“A Computer-Graphics Course for the Two Cultures,” Third International Conference on Computing in the Humanities, State University of New York (SUNY), Albany, NY, August 1977.

When I first started teaching, I was only – well – one or two years older than the students I was teaching. I thought, “Oh my goodness; they’re going to see through me, that I know nothing much more than they do, about what I’m supposed to pontificate.”

Collection of Aaron Marcus

Collection of Aaron Marcus

You met all these amazing people. That takes us up to what; 1972, ’73, ’74?

Suddenly Sheila de Bretteville, a very famous graphic designer and now Chair of the Graphic Design Department of Yale, which is completely coincidental, wrote me and asked me if I would like to go to Hawaii for a half a year as a research fellow. I said, of course, “Oh, yes. Why not?”

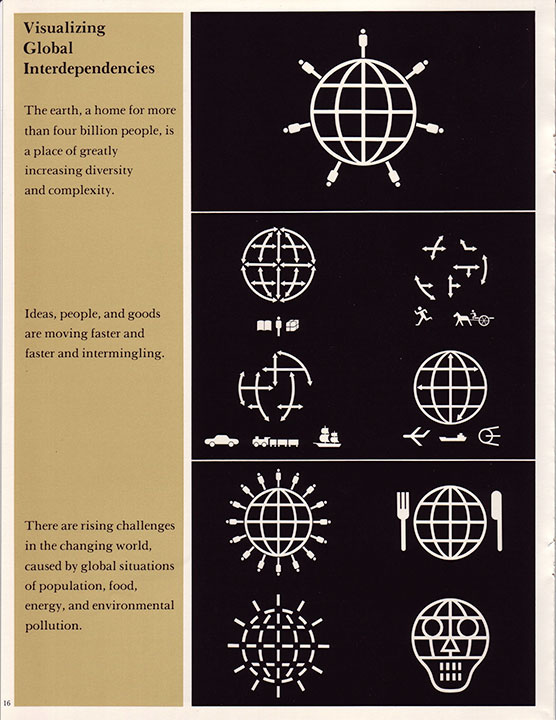

She didn’t want to or couldn’t do that particular activity. So I moved my family from Jerusalem to Honolulu and became a Research Fellow at the East-West Center, on the University of Hawaii campus, in order to visualize global energy interdependencies.

The East-West Center had been producing reports 600 pages long about all of these topics but few were reading them. So they decided to create a little project to see if they could create informational storytelling. That’s what we worked on for six months. [See the pdf of the publication that resulted.]

It also was an incredible, wonderful experience. I represented the entire United States. I had a friend representing all of Japan. A woman geographer representing China. An Indian audio/visual person representing all of India, and the translator of Marshall McLuhan into Farsi, from Iran.

If you’re trying to get together the replacement of a 600-page book into something in the format that people from all over the world will not only understand but be moved by, to affect change –

I should have said earlier, I’ve been interested since 1976 in semiotics, the science of signs, because I happened to meet Umberto Eco at Princeton, who is one of the great people of the field.

I realized in this project that we were trying to create visual storytelling, a sort of visual/technical communication that summarized hundreds and hundreds of pages of complex documents in presenting policies, world views, new technology, etc.

We were trying to communicate to world leaders, econometricians, and the person on the street.

I even later published a paper about the semiotic rhteorial tropes used in our presentation:

In fact the slogan for our company has been, “We help people make smarter decisions faster.” That’s what we were trying to do in ’78 in this audio-visual presentation. I had wanted to do it through computer graphics but the facilities at the University of Hawaii were just not sufficiently capable at the time, so it was done in a hand-crafted form from previous decades.

But we published the article about our work. It moved me towards a realization of what it was that I could do, and that led to my second ridiculous job interview at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory’s Computer Science and Mathematics Department.

I somehow convinced the head of the department, Carl Huang, to let me come in for a job interview…and I began with my classical words: “I don’t know why you would want to hire me, but I have this background, and I think I can help you in some ways to communicate the computer graphics systems you are developing.”

Luckily, he said ‘Okay; let’s give it a try.” Well, I realized I had about $4 million of computer equipment around me, not too far from Silicon Valley, and that they were building for the Department of Energy a multiple-database, computer graphics display-equipment independent software system that could munch on 60 different data bases at 60 different levels of aggregation and spit out charts, maps, and diagrams of any information obtained by the U.S. Government.

One of the first things they were doing was to try to produce for the public, U.S. Census data on demand. So it was a very democratic, in the ‘little-d’ sense, form of visual communication.

I wrote one of the first user interface design guidelines in 1979 – 80.

So, one of the tasks at that time was to design “a one-million page book.”

You were one of those people who sat in between computer graphics and coding.

That was partly through, say, a seminal publication by Jim Foley who wrote a great article in about 1976 about the fundamental concepts and terms and actions of user interfaces. I had contact with him all through the 1970s and 80s as his career progressed at Georgetown University and later at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

He along with others, like Andy Van Dam, another friend from early on in the ‘70s, created hypertext, created terms and concepts that helped people give names to these fuzzy phenomena that we all were encountering but may not have named in quite that way. Prof. Van Dam and I were in touch a number of times in the 1980s, and I wrote an article with him about the future of user interfaces in 1993.

Marcus, Aaron, and Van Dam, Andries. (1991, September). User-Interface Developments for the Nineties. ACM Communications, 24(9), 49-57.

In fact, one of the key things I’ve said for decades emerged in the 1980s: that user interfaces are essentially combinations of metaphors, meta-models, navigation, interaction and appearance characteristics.

I’ve been interested for a long time in metaphor design and metaphor concepts. It’s the search for metaphors that people stumble around and eventually find something that works that spreads rapidly, becomes a meme, becomes a paradigm, maybe even eventually a stereotype. But it’s that struggle to encapsulate essential characteristics in something that makes sense; that people can remember and learn easily, and that is appealing. Like the desktop.

Do you recall when you started to become aware of, or to help start developing a community of people in what we now call user interface design?

I remember going to the first conference before the CHI conferences came into being in 1982; SigCHi. SigCHI began in Gaithersburg, MD in 1982, and I attended that one.

In 1981 there was a pre-cursor conference in Ann Arbor, MI, of social scientists and others, who were thinking of trying to create an organization that would provide a home place, a home base, for people who were moving in these directions that were not considered “authentic enough” by computer-science departments or electrical-engineering departments or social-science departments or whatever you might mention. And certainly design schools and art departments were not ready for them.

For many years, for decades, SigCHI meetings were like being at summer camp. To be together with people who all were trying to understand how technology could be changed to be more humane; how various disciplines could contribute unique expertise and experience, and could come together to make cross-disciplinary contributions. Like what happens when we now take for granted all of the people who create a movie. All those credits that roll at the end. We don’t see that for user interfaces.

By the way, I also attended SigGRAPH conferences regularly too, which were also a kind of summer camp for the computer graphics people. However, a lot of artists, designers, and user-interface people “hung out” at that summer camp, also all through the 1980s and 90s.

Now, the fact is that some design does call attention to itself and that has value also: for being amusing, for making us self-aware of the artifact. But in many cases, certainly, if things are working well, we don’t even notice them.

IDEO was beginning to move into what I might have erroneously called “my turf” of user interface design. They were very successful. They had the marketing engine. They had the connections to corporate contacts. They had an established track record in product design and in industrial design, and they succeeded as did Hartmut Esslinger, the founder of Frog (59.32), and others, to create very large organizations.

Some of them didn’t survive. You may recall March First; do you recall that company?

Some of the large agencies have survived. We’re drifting into business territory here, but we survived because we were a “guerrilla group;” small enough to be flexible and to change our activities. We did a lot of work in the 1980s for R&D departments of NCR and HP and other corporate companies that eventually did far less of that R&D and outsourced it to start-up companies, which they could then conveniently buy.

We had to shift to more commercial projects, after our first 10 or 15 years. We still do a mix of corporate R&D, as well as work for start-ups and commercial product development. We also gravitated to a new component in addition to our tutorials — which had always been there but which is more evident – namely, creating executive marketing presentations for new technology.

The larger agencies were wise enough and capitalized well enough to continue growing. And they have now succeeded perhaps beyond their wildest dreams, because from my experience, a lot of corporate groups are so burned and frightened and understaffed that they only want to deal with very large agencies; that is, the larger corporations: fewer contacts and less paper work. It’s different for start-ups who can’t necessarily afford the larger design, research, and usability services.

So we have been excluded quite a lot because we’re not big enough, in the last three years, let’s say.

Basically large corporations wanted to outsource all the administration of multiple contracts to people and just have one large agency to deal with. But in fact what they’ve also created are substitute or virtual agencies that simply hire all of those smaller contractors –

I know we’re missing a lot of the more recent work. Perhaps we should do another conversation.

As you know, the title of this series of interviews is UX Pioneers and it really is talking to folks who have been absolutely instrumental in creating what we now call our field.

Is there anything else that you want to point out about your experience as one of the creators of this new field? Was there a particular time that you saw it really blossom?

And then people discovered, “Oh, wait a minute; that person’s stealing what I did.” A lot of protective barriers came up around things. But prior to that time, there was a kind of innocence.

It was charming. Perhaps short-lived. But for not only being in business but just staying in business, business attitudes had to prevail.

I would say that it’s been my experience that every five to seven years, there’s a new technology, a new thrill, a new bunch of newbies in the fields, and we kind of re-invent things again, often falling into some of the same patterns or mistakes, oversights, or tunnel vision that we’ve had before.

People then gain some maturity. The particular technology evolves and becomes more sophisticated, more humane, better designed.

People have forgotten, I’m sure, for the most part, the half decade of Video text and Teletext, which came out in the early ‘80s, I believe. Maybe late ‘70s but certainly early ‘80s … The displays were wild and crazy, and unsophisticated, and confusing, and terrible, because there were only eight colors that could be used, and everyone wanted to use all eight colors on every screen.

It takes a while for maturity to evolve.

Especially now that I am an elder, I naturally favor that opinion. …:-)…

If you could go back and tell that kid about something that you were going to do in the future in your career, what do you think would be the most exciting thing you could tell that kid about that you’ve done?

So finally, my last question, is what fascinates you today?

This particular person, now in Brazil, together with a colleague in Hong Kong, designed a headpiece that magnifies one’s eye blinking. So if you want to send a really strong signal to the other person, you can blink your eyes and your headset glows with LEDs that amplify the signal.

There are all kinds of things being invented that have to do with the body and outside the body that are intriguing.

As I‘ve mentioned, I’m also interested in all the work we’ve done with combining persuasion theory with information design in mobile technology to change peoples’ behavior; through these “Machine” concept-projects we are trying to figure out how a mobile device of some kind could help improve our bonding with other people, our general state of happiness, how we learn, how we drive, how we manage our finances, and how we tell stories.

Those have been the subject matter that we’ve been involved with on 10 different Machine projects. I’m trying to write that up into a book now called Mobile Persuasion Design, to be published next year by Springer.

© 2020 Adlin Inc. All Rights Reserved.

© 2020 Adlin Inc. All Rights Reserved.